Apache Kafka®️ 비용 절감 방법 및 최적의 비용 설계 안내 웨비나 | 자세히 알아보려면 지금 등록하세요

Journey to Event Driven – Part 1: Why Event-First Programming Changes Everything

The world is changing. New problems need to be solved. Companies now run global businesses that span the globe and hop between clouds in real-time, breaking down data silos to create seamless applications that synergize the organization. This continuous state of change means that legacy architectures are insufficient or unsuitable to meet the needs of the modern organization. Applications must be able to run 24×7 with 5-9s (uptime of 99.999%), as well as be superelastic, global, and cloud-native. Enter event-driven architecture (EDA), a type of software architecture that ingests, processes, stores, and reacts to real-time data as it’s being generated, opening new capabilities in the way businesses run.

Traditional vs Event-Driven Architecture

Traditional architectures simply cannot meet the challenges of real-time on mass scale. They have no mechanical sympathy and simply won’t work. It’s often said and well-proven throughout the NoSQL era that systems are designed to suit particular types of workloads and use cases. A time-series database isn’t very good at handling relational use cases or modeling, and likewise, a document database is great at structure, but not so good at analytics against those documents.

It sounds like a stretch of the imagination that any architecture could solve such extreme challenges. But fundamentally speaking, today, we are addressing these new, rising needs through microservices, IoT, event hubs, cloud, machine learning, and more.

At some point, it becomes obvious that we need to go back to basics, back to the first principles of system design, and start again. The common element of all these new world problems is that they revolve around the notion of real-time events. These events drive actions and reactions, and transform between different streams, splitting, merging, and evolving like the pathways of your brain.

Importance of Event-Driven Architecture

To understand the importance of being event-driven, we’ll examine why events have become so pivotal in our thinking today. We will then evaluate the qualities and how events have become a first-class concern for the modern organization, as awareness of events underpins event-first thinking and design. I’ll then extrapolate design concepts against different perspectives of event patterns, such as the event command and event first, and why event-driven programming fulfills foundational requirements when choosing an architecture that supports evolution and elasticity.

Overview

- An opinionated history of “events” – Why do they matter?

- Adoption journey of the “event”

- Considerations of the event-driven architecture

- Transitioning to event-first thinking

- Event-first versus event-command patterns for event-driven design

- Event-command pattern

- The cost of the event-first approach

- Benefits of the event-first approach

To read the other articles in this series, see:

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 2: Programming Models for the Event-Driven Architecture

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 3: The Affinity Between Events, Streams and Serverless

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 4: Four Pillars of Event Streaming Microservices

An opinionated history of “events” – Why do they matter?

It’s taken the last 25 years to get to the point where we consider the event as a core principle in system design. Throughout that period, much of the world was stuck thinking that remote object calling was the right way of doing things. REST and web services started by exposing the API as a concern, but that was done by a synchronous protocol.

In 2002, I built a commercial messaging system that adopted principles from the SEDA: An Architecture for Well-Conditioned, Scalable Internet Services paper—the idea being that we move everything to become asynchronous; local and remote events are then used to drive the intelligence and adaptation of an application. It really shaped the way I understood events to be a core design principle as well as how to think about system design and data in general.

There has been a revolution; organizations must become real time; to become real time, they must become event driven

It took the era of big data for us to realize that while having lots of data is useful, things get slower as you have more of it. And yet, we collect more. Over the last several years, there has been a revolution; organizations must become real time; to become real time, they must be event driven. This need is fueled by the increasingly digital world that we live in where everything is connected. Events are a fundamental aspect that drives this ecosystem; an organization is but a cog that when viewed at any level needs to act and react to internal and external events.

The value of events is that a sequence of related events represent behavior (e.g., an item was added and then removed from a shopping cart, an error recurs every 24 hours or users always clicks through a site in a particular order). A sequence of related events is commonly called a stream. Streams can come from an IoT device, a user visiting a website, changes to a database or many other sources. When thinking of APIs, we start with the event rather than the highly coupled concept of a command, e.g., an event-X has occurred, rather than command-Y should be executed. This thinking underpins event-driven streaming systems.

A stream of events captures temporal behavior

Adoption journey of the “event”

There are many paths to the inception of an event-driven architecture within an organization. For some, it is a natural pattern evolving from domain-driven design (DDD) principles, the related and powerful event-storming practice, decoupled systems design, or just event-driven microservices. The point is they can come from any level, whether business or technical, but it will be a conscious adoption that doesn’t just happen by accident.

Considerations of the event-driven architecture

There are many considerations when evaluating the event-driven architecture. Events initially start out to as atomic and drive reactionary callbacks (functions). As a use case evolves, workflows develop and the criticality of the application generally increases along with the nature in which an event is considered. This raises numerous questions. Is ordering important? Do I want to ensure transactionality? How do I trust the execution? Security? Lineage? Where did the event come from?

The key realization for the adoption of event-first thinking is that an event represents a fact, something happened; it is immutable and therefore changes how we think about our domain model

The basic attributes of an event include time, source, key, header, metadata and payload. One problem with events is that they are everywhere, and the extreme lack of consistency makes them very difficult to work with at scale. In an effort to solve this, CloudEvents 0.2 was released by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) in December 2018.

A CloudEvent is a standard event envelope containing sufficient information for any consumer to use correctly (schema, source, etc). The most interesting note is that the CNCF Serverless Working Group is standardizing the serverless model to encompass how CloudEvents work with FaaS functions, function signatures, workflow, extensions, transport bindings, SDKs and more. The future of serverless will be one where FaaS functions can work together across cloud boundaries, the enterprise and all corners of the globe. It is pretty exciting.

The heart of FaaS will beis the CloudEvent

The other consideration is that events do not exist in isolation. Due to their very nature, an event tends to be part of a flow of information, a stream. We define a stream as an unbounded sequence of related events that are associated through the use of an “eventKey,” a key that ties multiple events together.

In the real world, the nature of the “event” can be described as:

- Atomic: something happened (bid on an item, send an email, device temperature)

- Related: a stream or sequence of events (tracking a pricing change, device metrics changes over time)

- Behavioral: the accumulation of facts captures behavior

Behavioral is the least obvious but most important aspect of event-first thinking. For example, in a shopping cart, if an item was added and removed—and this has occurred among many users—then we have captured a behavior. By analyzing the sequence across many users, it is possible to discern whether they changed their mind due to targeted advertising, finding a cheaper price elsewhere or perhaps because it is close to an annual event like Christmas, a birthday, etc. Ideally, the system should detect the behavior and react to it, as capturing events has a great deal of implicit value.

Transitioning to event-first thinking

Event-first thinking changes how you think about what you are building

The adoption of event-driven architectures tends to result from an “aha” moment, which involves moving from simple, use cases to a deeper understanding of processes, operations and how to reason about the architecture.

You may start off creating the event streams required to build an application to fulfill your original design goals, but quickly find that the event streams themselves enable you to build much richer, totally unexpected analysis and functionality.

How is the event treated within a system? All of the following questions get asked as the event-driven architecture is developed:

- Is it observable, and are the flows of streams behaving as expected?

- Is it trusted, meaning transactional, exactly one or at least once? Will it scale?

- Is stateless processing, such as filtering, projection, cleaning or enrichment required? Is stateful processing, such as aggregations or stateful sequence processing required?

- Is a materialized view against the stream required? How many transactions per second are required for a windowed view?

- Do we want to scale/fan/map out (parallelize), fan in/collect and, build materialized views?

- Does it support error handling, such as error flows and dead letter queue?

- Does it send and transform events from one stream into others (stream processing)?

- Does it react and drive intelligence from the state collected from a stream (stream processing)?

In terms of increased adoption, we generally see these patterns as characteristic of an event-driven organization:

- Data pipelines (ETL, integration)

- Monitoring and alerting, including log collection and aggregation

- Event-driven microservices

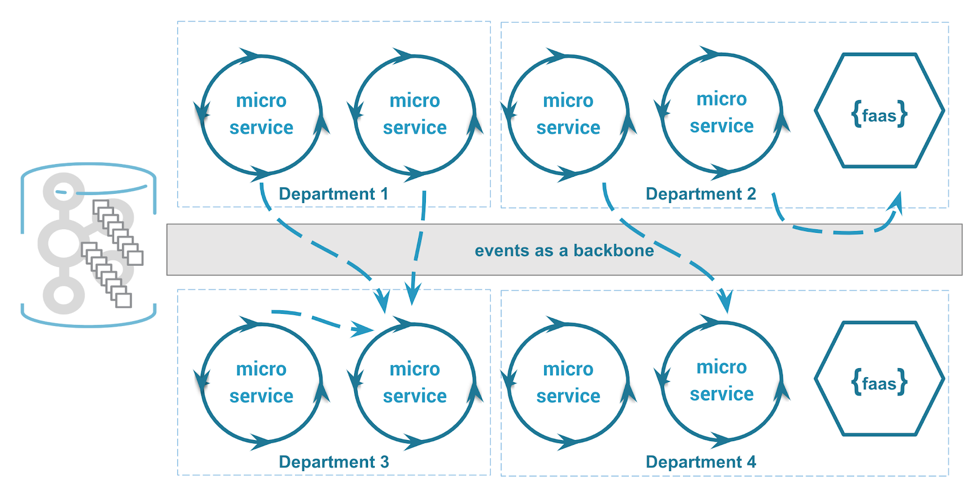

- Enterprise wide event-driven microservices

- IoT

- Customer 360

- Digital transformation

- Real-time enterprise

- Central nervous system/digital nervous system

By embracing event-first thinking, we naturally inherit the foundations of event streaming platforms like event sourcing, replayability, stream processing and dataflow design, amongst others. We should also incorporate event-first thinking into an architecture that leverages a serverless stack to be event driven, multi-cloud and elastic.

There are several ways to be event driven. Without becoming tangled up in the marketing noise, we can boil it down to a couple of approaches. The first reuses messaging principles and sends pure events like item-purchased, while the second reuses the conventional, more familiar approach of sending commands as events, like user.purchaseItem(item). Both can be event driven, but the design principles are fundamentally different. Let’s expand on this thinking to understand the impact of both approaches.

The importance of events and event first thinking:

- Capture facts

- Capture behavior

- Provide a representation of the real world

- Model use cases of how we think

- Supports repeated evaluation and processing (a time machine)

- Provide horizontal scaling

- Speak the same language as the business

Event-first versus event-command patterns for event-driven design

You can build the same application using either the event-first or event-command approach, but the event-first approach is generally recommended. If we rewind onto familiar ground for an example, we see that traditional REST applications are an event → command pattern. They are coupled in multiple ways: Firstly, the endpoint is known (i.e., the service address). Secondly, the method being called is also known (i.e., an API call to doStuff), and lastly, the calls tended to return a value; they are synchronous. Newer frameworks will allow this call to be handled synchronously or asynchronously—it is called the event-command pattern.

Alternatively, with the event-first pattern, the paradigm shift is to discard all of those considerations and just send an event as we would in the traditional messaging sense; don’t do anything else; have no API coupling to a remote service. The approach is unique in that it processes the event as a reaction; the emitter doesn’t call on a specific function; the API has been removed and it instead just sends an event. The emitter of the event doesn’t know which processors (or functions) are going to consume it, and the event becomes the API. This decoupling allows the set of consuming apps to change over time without any upstream changes required in the emitter.

Event-first analog: I walk into a room, generate an “entered room” event and the light turns on. This is a reaction to an event.

Event-command analog: I walk into a room, flip the light switch and the light turns on. This is a command.

In the event-first analog, I have no knowledge and don’t ask for the lights to be turned on;. Instead, a sensor detects my presence; it has the responsibility. In the event-command analog, I have the responsibility of knowing how to turn on the light and also making it happen.

The event-first approach forces an inversion of responsibility; it is a fundamental paradigm shift of how applications are developed

Let’s apply it to a business function.

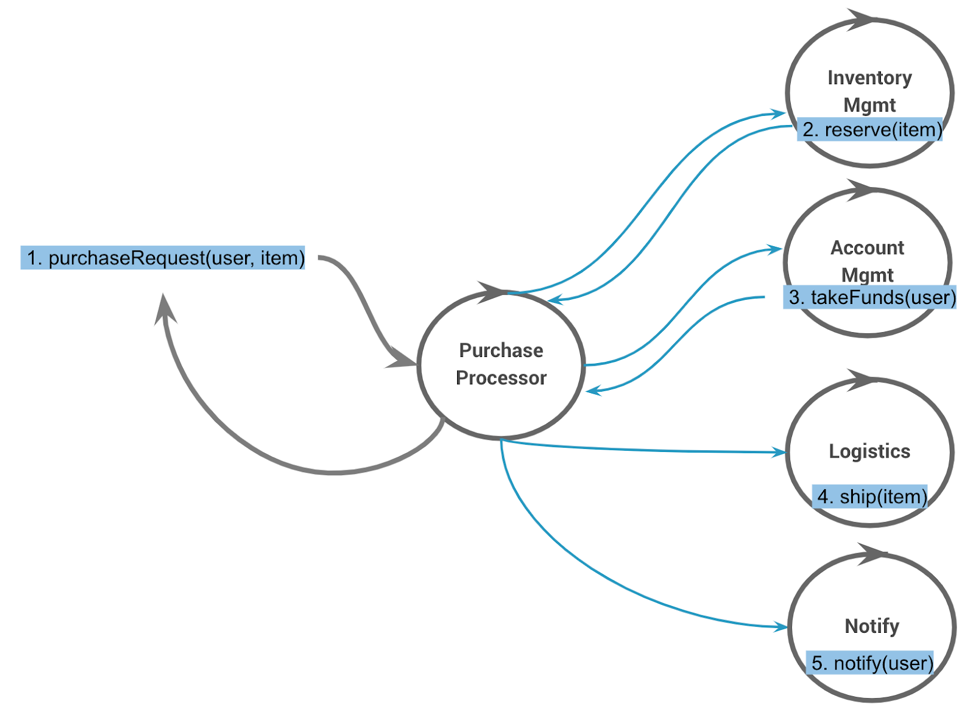

Event-command pattern

In the event-command pattern, the service knows the endpoints and API of the other services and calls them. For example:

Event-first pattern

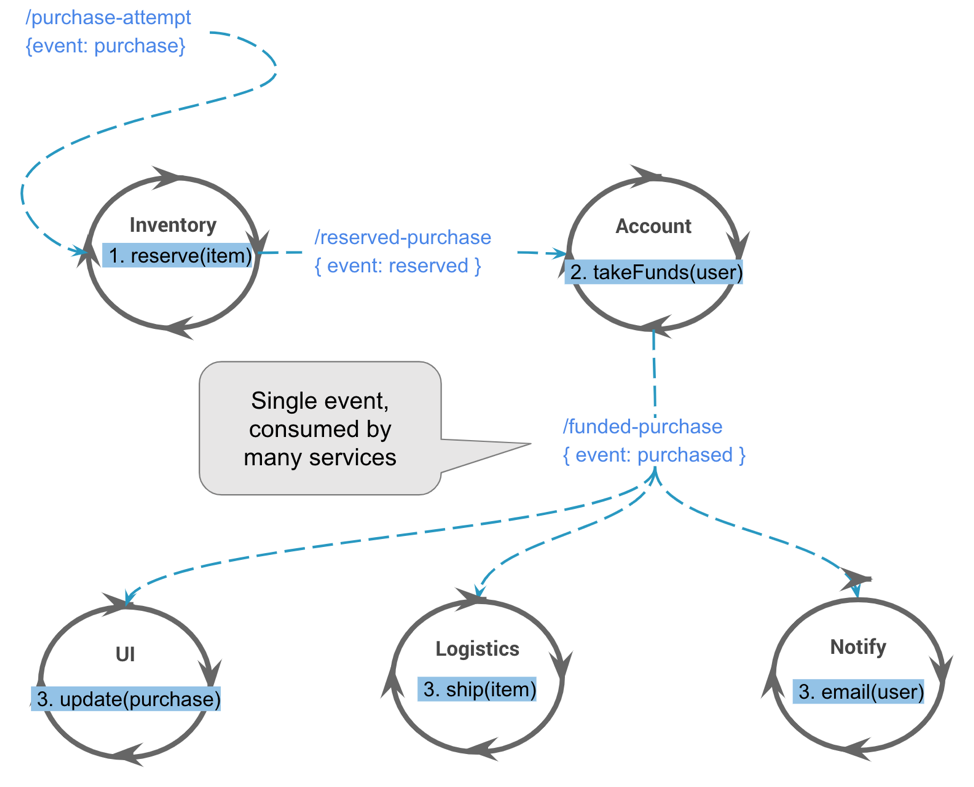

With the event-first approach, each service listens for inbound events and outputs zero or more events after performing some (re)action. For example:

At this point, the two approaches don’t look that different. If anything, the event-first approach looks more complex, as it has to more moving parts, e.g., publishing/consuming events via streams. The benefit is that these streams provide decoupling.

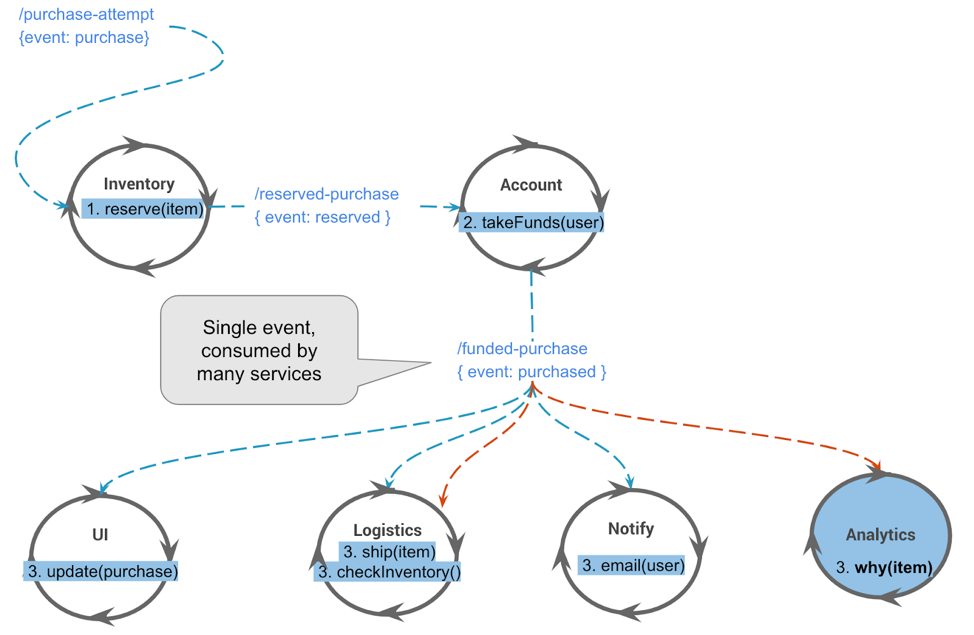

The power of the event-first approach becomes clear when we try to enhance the system. Let’s say we want to add the ability to check inventory levels and reorder stock when levels are low, to perform analysis on the cause of failed purchases and help improve conversion rates.

For the event-command-based system, we need to change the main purchasing application to call these new systems. But for the pure event-first solution, we can simply add new processors of the existing events, such as why(item) and checkInventory().

Notice how the event-driven approach allows many processors to react to the same “purchased” event (published via the /user-purchases topic)? This flexibility means functionality can run in parallel and be added, extended, upgraded or replaced without taking the system down. Decoupling is the key. The “event” also affords the opportunity to propagate versioning, security tokens, correlation IDs and other useful information.

The cost of the event-first approach

The tradeoff of the event-first/event-driven architecture is the amount of scaffolding required to inspire confidence. In the old days when transactional consistency shaped our expectations, and NoSQL pushed us to eventual consistency with CAP theorem tradeoffs, it was known that data wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) get lost. Event orientation requires not only different thinking in replacing the command model but also the ability to support traceability, failure paths, scaling and explanation about why things have gone wrong. These challenges are easily solvable and are also quite fun; I will revisit this topic later on.

Benefits of the event-first approach

The pure event-first approach described above demonstrates:

- Decoupling: Processors don’t know anything about upstream or downstream processors

- Encapsulation: There are clean boundaries between processors.

- Inverted knowledge: Knowledge and responsibility are reversed.

- Evolutionary change: The system and events can change over time.

- Event sourcing: When using a log and log-aware stream processors, we gain the ability to potentially rebuild and restore application state. It’s not a free lunch; the application state needs to be captured and managed.

Evolutionary architecture is a natural benefit from event-first thinking and event-driven architectures

When you use the pure, event-driven approach, the architecture can change over time as different processors may react to events, which can be reprocessed while the data model evolves simultaneously. Perhaps the domain model has changed, or functionality is being extended. None of the originating events are lost, and the behavior is captured in the stream. With these foundations, you then have a system that supports architectural evolution as well as data and domain evolution.

For a deep dive on events versus commands, check out Ben Stopford’s article Build Services on a Backbone of Events. Rebecca Parson, Neal Ford and Patrick Kua also wrote a great book on these principles called Building Evolutionary Architectures. If you’d like more background reading, Martin Fowler’s blog post Focusing on Events paints a nice story too (albeit it was written in 2006).

To support the event-first approach you need a suitable platform. Evaluating the pros and cons, knowing where to start and understanding the ecosystem and everything else that goes with that decision is in and it of itself a complete mission. There are a plethora of blogs and vendors creating noise that crowds and confuses the market.

I personally deplore anything that resembles a framework; they are the pinnacle of IT gone wrong. I’ve spent too many years upgrading from one framework to another only to be stung along the migration path.

The ideal solution is one where the stack is simple, the surface area is small and I the developer retain control. This normally dictates some form of the programming model, and as distributed computing moves to its next generation, we also need to choose something that is forward looking. It must fit with the types of distributed applications that we need to build for tomorrow and not constitute a retrofit of old-school RPC.

Finally…

I have reasoned about how event-first thinking represents a new opportunity, a new frontier for technology and businesses to go back to first principles of system architecture and design. Changing the underlying foundations of how we conceive technology naturally shapes how we approach business problems, and therefore how we develop technology.

This revaluation on technical design pushes us towards a pure eventing model where we throw out the event-command pattern and simply emit events. The benefit of this approach meets many modern requirements where systems are elastic, easily composible, expected to run 24×7 and, most importantly, are evolvable. The ability to progress domain models that are supported by events and remodel event streams is an essential requirement for the modern business.

It’s not a free lunch, however. With the event-first model comes the need to build trust and confidence that the system not only scales but also functions as expected, which is kind of important, right?

I hope you join me in part 2 of this series, where I’ll walk through different styles of event-driven architectures. Choosing the right style of architecture is as important as the realization of becoming event driven, with each approach having various pros and cons. The conclusion isn’t surprising, but the world is changing, and we need to understand technology through a new lens. Just like learning a new programming language, we need to try and push our predispositions aside, and embrace the anarchy of thinking and rationale!

Interested in more?

If you’d like to know more, you can get started with Confluent, the leading distribution of Apache Kafka® and run through the quick start.

In episode 18 of the Streaming Audio podcast, I also discuss the future of serverless and streaming with Tim Berglund.

Other articles in this series

이 블로그 게시물이 마음에 드셨나요? 지금 공유해 주세요.

Confluent 블로그 구독

Unlocking Data Insights with Confluent Tableflow: Querying Apache Iceberg™️ Tables with Jupyter Notebooks

This blog explores how to integrate Confluent Tableflow with Trino and use Jupyter Notebooks to query Apache Iceberg tables. Learn how to set up Kafka topics, enable Tableflow, run Trino with Docker, connect via the REST catalog, and visualize data using Pandas. Unlock real-time and historical an...

Shifting Left: How Data Contracts Underpin People, Processes, and Technology

Explore how data contracts enable a shift left in data management making data reliable, real-time, and reusable while reducing inefficiencies, and unlocking AI and ML opportunities. Dive into team dynamics, data products, and how the data streaming platform helps implement this shift.