Journey to Event Driven – Part 2: Programming Models for the Event-Driven Architecture

Part 1 of our series on event-driven architecture discussed why you need to embrace event-first thinking, while this article builds a rationale for different styles of event-driven architectures and compares and contrasts scaling, persistence and runtime models. Once settled on the event streaming approach, I’ll provide a high-level dataflow of how we design systems for payment processing at scale using this approach.

The paradigm shift to the event streaming architecture often leads to a lightbulb moment of inspiration and clarity.

I will then wrap it up by composing the beginnings of a solution architecture that walks through the event streaming app, but also attaches event-stream patterns for “running on rails” in addition to instrumentation, data and control planes. In this way, we don’t think about solution architecture in just one dimension. Rather, we apply different event planes to provide orthogonal aspects of system design such as core functionality, operations and instrumentation.

Overview

- Event-driven architecture

- Event-driven, reactive architecture

- Event-driven, streaming architecture

- Comparing persistence models

- Do I need to use a microservices framework?

- Stepping through an example of an event streaming app

- Being event first

- Data evolution

- The future of programming

To read the other articles in this series, see:

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 1: Why Event-First Thinking Changes Everything

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 3: The Affinity Between Events, Streams and Serverless

- Journey to Event Driven – Part 4: Four Pillars of Event Streaming Microservices

Event-driven architecture

Programming models have evolved over the years. Distributed object (RPC sync), service-oriented architecture (SOA), enterprise service bus (ESB), event-driven architecture (EDA), reactive programming to microservices and now FaaS have each built on the learnings of the previous. We’ve quickly learned through microservices and SOA with the traditional model that RPC-based systems don’t scale, and managing state and correctness also doesn’t scale. Without conflating the two, let’s first focus on scaling event-driven architectures.

Event-driven, reactive architecture

Simple event-driven architectures were introduced many years ago. We first saw them gain mainstream popularity as part of the ESB phase. The approach of this model is to send messages (events) to different services that can react and execute logic. It serves as a conduit to drive distributed logic (event processing), and messaging is a remote invocation layer. The actor model is a variation on this idea where it is a means of distributed computation. The event-driven, reactive model was further standardized and adopted when the Reactive Manifesto was in full swing.

Systems built as Reactive Systems are more flexible, loosely-coupled and scalable. This makes them easier to develop and amenable to change. They are significantly more tolerant of failure and when failure does occur they meet it with elegance rather than disaster. Reactive Systems are highly responsive, giving users effective interactive feedback.

The Reactive Manifesto has influenced many frameworks and platforms, including Akka (an actor-based library circa 1973), Vert.x (reactive microservices) and Lagom (an opinionated, reactive microservice framework). Although the principles behind event-driven frameworks are sound, those behind event sourcing, CQRS and hydrating application state are separate concerns so we often see them handled explicitly as an orthogonal concern (e.g., operational processes) or externally (think GitHub for your applications state).

Scaling mechanism

The Akka scaling mechanism uses a cluster service which pools actors from remote nodes that join as cluster members. Inactive actors are persisted to disk to minimize idle resource requirements. The cluster is elastic, provides resilience and provides the distributed runtime for making the Akka system scale. Scaling actors is achieved by increasing the number of actors—effectively increasing the event processing capability of the application, not the data. Persistent actors will store their set of events to a journal (log). Akka Streams then changed tact as streaming became the core mechanism to drive processors in a more data-centric manner.

Event-driven, streaming architecture

With the event-driven streaming architecture, the central concept is the event stream, where a key is used to create a logical grouping of events as a stream. We think of streams and events much like database tables and rows; they are the basic building blocks of a data platform. Streams represent the core data model, and stream processors are the connecting nodes that enable flow creation resulting in a streaming data topology. Stream processor patterns enable filtering, projections, joins, aggregations, materialized views and other streaming functionality. Unlike the previous model, events are front and center.

The event streaming platform is effectively a data platform and therefore behaves accordingly. Data models need to be developed in relation to use cases. A streaming application can be thought of as a dataflow system. For example, a stream can be used to capture patterns such as a user’s clickstream, a set of events against a transaction, shopping cart behavior, etc. In this case, “events” drive the event stream.

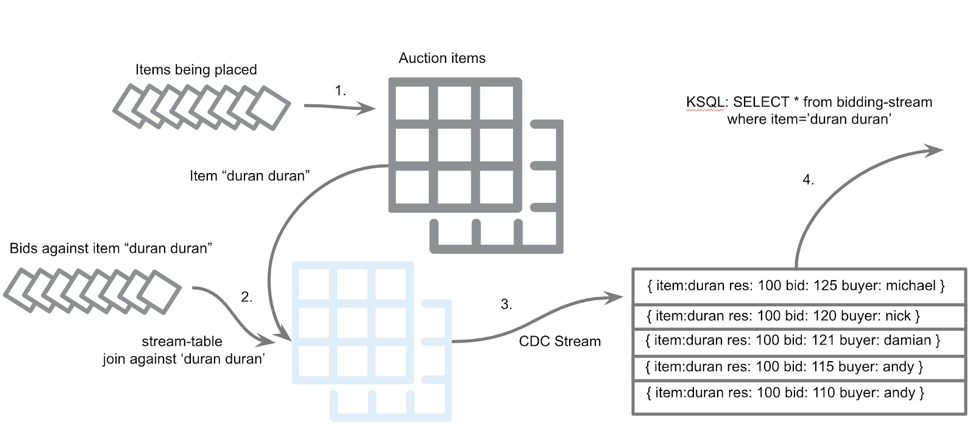

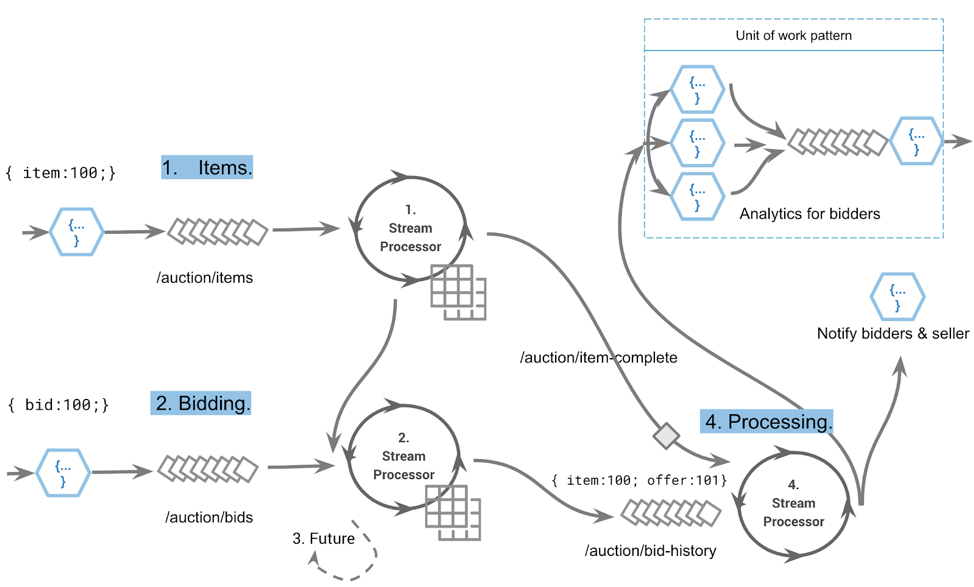

An event streaming application depicting auction-bid functionality

The streaming topology shows a flow of data through an organization, representing the real-time DNA of your business. A proven approach is to capture domain knowledge as events using domain-driven-design (DDD) and event storming. This approach works well because the events-centric view forces the use of a ubiquitous language; the business, technologist, developers and ops all have a common understanding of the system’s functions.

An event streaming app: streams and stream processors modeling an auction platform bid functionality

Stream processors can also be used to materialize tables from the stream of events to enable a view of the data (e.g., how much money was in my account at time X). The term is called turning the database inside out. Stream processors are used for constructing the flow from other streams in various patterns, either executing and reacting to logic or splitting, merging and maintaining materialized views, such that when they are all combined (fan in), they represent a domain model in the form of a digital nervous system.

Like database transactions, stream processors can also transact against the event log, support correctness semantics like ordering, exactly once semantics (EoS), idempotence, temporal reasoning and more. Unlike a traditional database, the platform scales horizontally to thousands of processors, observe real-time events, replay streams on demand to perform historical event processing and catch up with the live, data-in-motion view.

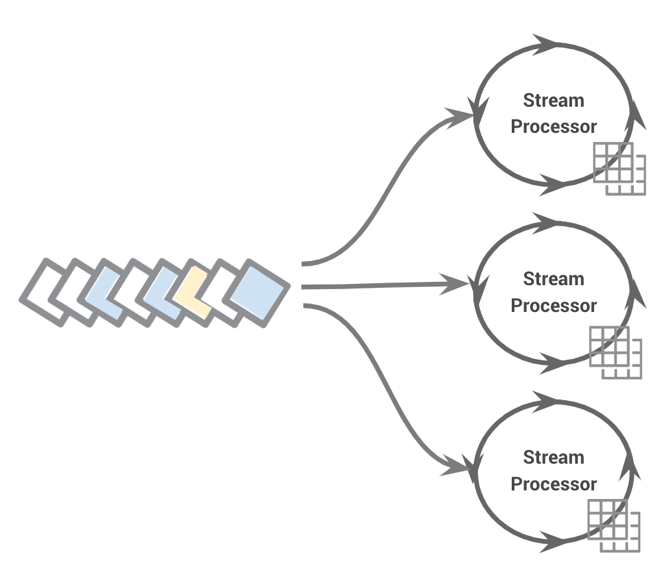

Materialized views scaling against a stream

Streams processors store their fair share of data locally; in combination, they form a distributed data layer

The stream is like a database table, whereas the event streaming platform is a data platform. As such, we model the domain with event-first thinking. A common use case that trips up those who are new to the concept is payment processing. A traditional OLTP system uses a two-phase commit to move money from a debit account to a credit account. It is very simple but presents scalability challenges. In the event-driven world, we’d build a scalable model where the event streams flow between event processors. By the end of the flow, the payment is transacted.

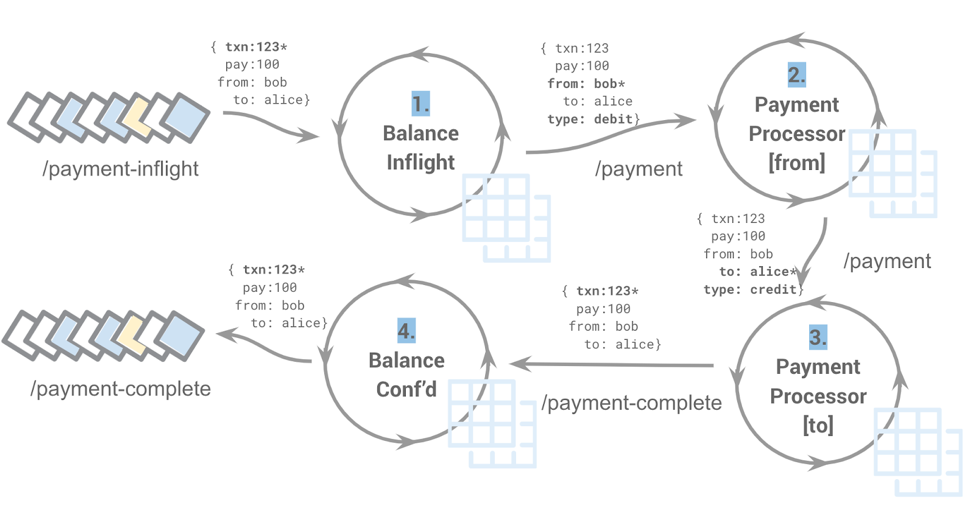

Event-driven payment processing

Let’s walk through the flow of the above diagram:

- Payment requests flow from the /payment-inflight topic into the balance in-flight processor. It maintains a view of the total balance, including those currently being processed, similar to a read-uncommitted view. It sends the payment request into the /payment topic, keyed by the “from” account and setting the event type to DEBIT.

- The payment processing picks up the DEBIT request and validates that the payment can be processed, updating the user’s balance in the materialized view. It then emits another event, keyed against the “to” account and setting the event type to CREDIT.

- The payment processor receives the CREDIT event, updating the user’s balance in the materialized view, and passes on the payment-complete event.

- The Balance Conf’d stream processor updates the total confirmed balance similar to the read-committed value.

- The two balance processors are different instances of the same stream processor. The difference is that while one is aggregating the system payment, balance as a total, the in-flight processor is consuming the payment-complete values. The balance processor tables can be queried using interactive queries, and the difference is the current amount being processed by the system.

Scaling mechanism

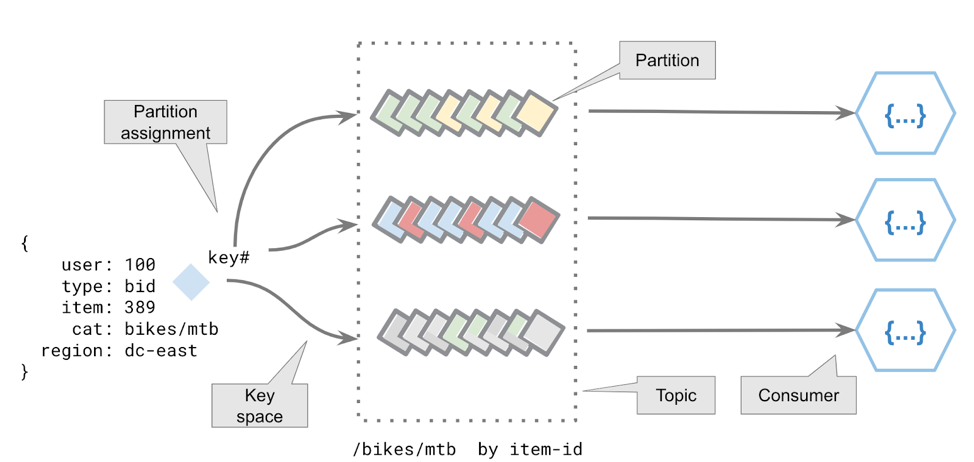

Scaling is the opportunity to send concurrent streams from thousands of producers to thousands of consumers. Populating a stream with real data as shown below lets us understand how the data is distributed in order to support horizontal scaling. To achieve scaling the underlying event streaming platform will use partitioning (sharding) to act as buckets for streams to be stored in. The broker sizing is a function of the total sum of partitions across the number of servers and replicas.

To map a stream of events in a single partition we use an eventKey. The eventKey acts to identify a set of related events as a stream. Events never occur in isolation. There is always a context for triggering the event, and the eventKey captures this identifier. An example might be an IoT device, transaction-id or some other natural key. To determine which partition is used for storage, the key is mapped into a key space. This key mapping uses a partition-assignment strategy (the default provider uses a hashing function).

It is important to note that a partition can only be consumed by a single consumer; however, a consumer can consume from multiple partitions. Consumers in this context are anything that requests data; they could be stream processors, Java or .NET applications or ksqlDB server nodes.

Horizontal scaling is achieved via partitions. Each partition will hold multiple streams (streams are color coded).

I won’t go into this topic any further, but suffice it to say, key space is of fundamental importance (as well as having sufficient partitions). While we see partitions becoming cheaper, the number of partitions (shards) should always be much greater than the number of stream processors or FaaS functions required to support scaling of unexpected workloads.

Comparing persistence models

Persistence with the streaming model is significantly different to other approaches (actor, reactive, external DB). In non-event-streaming platforms, the persistence model is part of the framework or is a deliberate intent to interact with an object. For example, with Akka there is the “actor entity” (using a persistent actor or distributed data). In this approach, you program an entity, and there is a binding to the underlying persistence layer, such as the following:

creditCardActor.get(123).deposit(456).

The actor can also emit an event to a view layer thereby enabling CQRS.

The streaming model doesn’t use an entity as a programming model in the same way. It’s more in line with a data processing approach, where the incoming stream represents events. The event processor updates the local state accordingly and emits related events.

For example:

/deposits-topic { card:123 deposit:456 } →

cardProcessor.updateCard(123).deposit(456) →

/card-balance-topic topic event:{ card:123, balance:456}

The entity state is maintained by the event processor using the the incoming stream, and updates are sent to the output stream. The entity is implicit in the stream, and the materialized views provide a particular view against the stream, such as min, max, avg and current value.

With stream processing, the log stores the truth for the entity; it is organized as a stream. The log (stream) also stores every version of the entity.

Let’s summarize the persistence aspects:

- The event captures facts about an entity within the domain.

- The event stream is a journal of events, it is the transaction log.

- The event stream captures behavior.

- Event streams provide a model for scaling horizontally as well as performing local processing.

- Materialized views let the processor maintain a local state. Jay Kreps provides an in-depth view and rationalization on how this works with streaming.

- External sources can be materialized using connectors providing yet another streaming source of data accessible by the same data plane (streams and stream processors).

Because the orientation of the event streaming platform is event data, it brings with it a wealth of other functionality that I would encourage the interested reader to research further: Streams can be queried using SQL (ksqlDB); stream processors can perform data-local processing (colocated microservices and data) to support throughput and everything becomes observable by leveraging other streams (metrics, logs). I’m limited to space so will briefly mention Confluent Schema Registry, data evolution (schema evolution), change data capture (data virtualization), event collaboration and coordination primitives, streaming patterns, evolutionary architectures, disposable architectures and event tracing (correlation IDs).

Do I need to use a microservices framework?

Many people start looking at stream processing through the lens of microservices. They believe that streaming should accompany their existing microservice framework. This is not the case; the event streaming platform will replace it. We think of stream processors, producers and consumers as microservices.

The event streaming platform provides the means of storing data as a stream and streaming events at scale. In order to facilitate this functionality the underlying protocol needs to ensure qualities such as offline status, different consumer rates, high throughput, low latency and elasticity (amongst others). The consumer model is one which exposes the protocol to the developer; this means the consumer will have the opportunity to ACK, NACK message receipt and interact with the correctness of accepting a message payload.

In some cases, it is desirable to hide these protocol concerns. In such cases we recommend the StreamProcessor approach. The benefit of this approach is that it intrinsically supports filtering, transformation and also stateful operations against streams. There is no need for other frameworks to apply their “magic” on top of Apache Kafka® but instead stay in the pure event-first paradigm. Classic microservice concerns such as service discovery, load balancing, online-offline or anything else are solved natively by event streaming platform protocol.

We also hear about backpressure being a concern to control event throughput. I would question if this is actually a requirement or marketing speak. Brokered systems like Kafka provide huge buffers (the default in Kafka is two weeks) which negate the need for explicit flow control for the vast majority of use cases. In the very few that remain you can easily build backpressure as a control plane detail; it would be developed using stream processors that analyze throughput patterns of events and apply rate limiting events to the relevant producers.

You don’t need another microservice framework when you use Kafka; the streaming protocol natively solves all conventional microservice concerns

Event sourcing is also another mechanism that can use a specific event sourcing framework or be built into various microservice implementations; think of it like GitHub for your application runtime state ;). With Kafka you get event storage for free; this is different. Every producer, consumer and stream processor persists its state into a Kafka stream.

However, for event-sourcing, things get more complex; the ability to rebuild application state on demand needs a dedicated framework and process control to ensure point-in-time or snapshot state is correctly rebuilt. You cannot simply start replaying events from an offset and expect the downstream aggregates to be deterministically reproduced as they were previously. There is replaying from the beginning of time and replaying from a point in time; they are not the same thing.

Imagine if the balance of your bank account was suddenly reset to zero yesterday—what happened to the previous state? With event sourcing, the previous state is captured and used as the starting point. This is a fairly large topic, and it is common to rebuild stream processing state stores from external state or roll out your own using Kafka Streams. It is a topic that is “trending.” For more information, look at event sourcing projects like EventStore and dive into this blog post.

Stream processor stateful operations like join, enrich, window, aggregate, etc., are stored at the partition level, which means they can be resized according to throughput and carry on processing patterns without missing any events. A single stream processor instance might be operating against five partitions before it is shut down, and then five are started to replace it. Those five instances will load the relevant partition state from Kafka changelog topics and continue stream processing.

All of the trust and resilience is based upon the event streaming platform’s correctness and guarantees of working with the commit log.

The final point on this topic is one which is often overlooked, and that is the language ecosystem. There are a myriad of clients (producer and consumer) in languages from Java, Scala, Python, Node, .NET, Python and Golang. They all use the native streaming protocol which means elastic scaling, commit log correctness and all other guarantees are supported. In terms of stream processing support there is Kafka Streams in Java, Scala, Goka (a Golang implementation) and also a less complete derivative in nodejs.

Stepping through an example of an event streaming app

Let’s combine all of the preceding concepts into a solution architecture. I‘m going to present a single use case that captures the essence of everything discussed thus far—namely, how I compose a business function of streams and stream processors.

This approach addresses:

- Core function: Building an event streaming model for item bid activity and placement

- Trust: Run it on rails with instrumentation and throughput monitoring

- Control: Offline and rolling restart

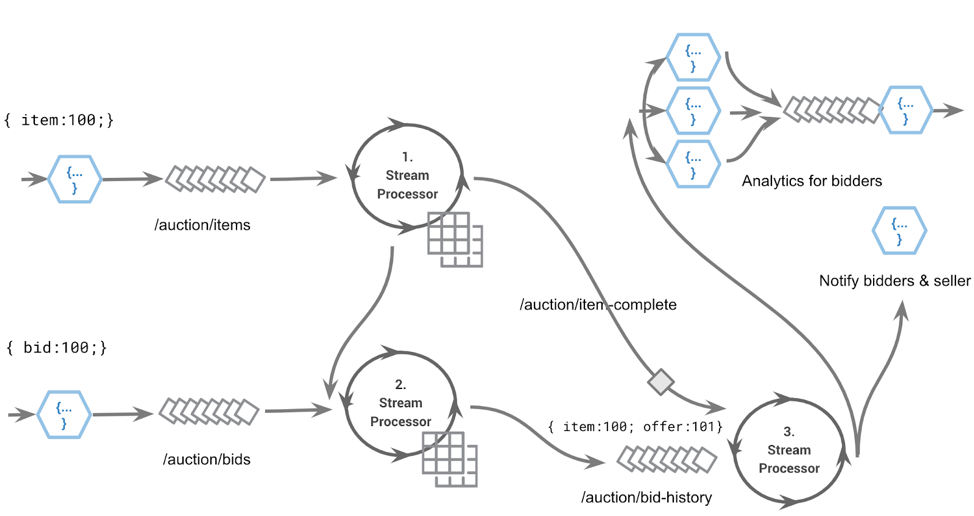

1. Core function: Building the event streaming model for item bid activity and analytics

A user bidding app, which is part of the auction platform

Let’s step through the above event streaming application:

- This FaaS function will enrich, filter, geo-encode and validate the item before it is accepted into the items stream. FaaS is a good fit because it is at the edge, and there won’t be competing events, i.e., the same user won’t submit the same item within milliseconds of each other. Once submitted, we enter the world of streaming. A stream processor instance is running a queryable KTable of items that can be used to query against available items.

- Our next flow is the bidding against certain items. At this point, the client has queried the available items and is submitting bids to the /auctions/bids topic via a FaaS, which enriches the event to a geo-IP grid or provides address validation. The stream processor joins this stream with the items, creating an audit of bidding history stored on the /auctions/bids/history topic.

- To determine when an item has expired (sold, unsold, reserve not met), each stream processor runs a future against its locally held item table (materialized view) so that upon completion, the original item is updated to break the join between steps 1 and 2 (i.e., join where item.status != complete).

- The change of item condition emits an new event to /auction/items-complete that executes the item-complete processor. It looks at the bidding history where a series of FaaS events are triggered.

The FaaS analytic function group in the top right of the diagram receives the entire history of related events, generates bid offer spread analytics and notifies the users of how the auction played out. The notification FaaS function simply emails the bidding users in response to the initial set of success or failure events. In other words, you either purchased this item or you were outbid.

This functionality can be extended in many ways. We can leverage the live bidding stream for ad placement to attract bidders to similar items as the bidding time comes to a close, or set their expectations about the historically successful price range of similar items.

2. Trust: Run it on rails with Instrumentation and throughput monitoring

It’s always important to understand if the event streaming application is performing, if it is meeting throughput requirements and provides sufficient insight about how it is meeting business SLAs. More importantly, many newcomers to event-first design get extremely concerned about knowing that an asynchronous application is actually performing, failing or just working as expected; they don’t trust it. This is because event streaming apps need to be “run on rails.” You not only monitor the happy path but also track all other aspects like error handling with dead letter queues, business metrics and flow metrics.

![]()

Instrumentation plane tracking application-wide metrics

Business metrics are collected by stream processors to aggregate the data patterns and mapping them onto end-to-end business flows; these flows are identified by the source and elapsed milliseconds. Outliers are identified by tracking end-to-end latencies and drilling down to flow level metrics.

Flow metrics are the tracking individual components (microservices) where outliers and other analytics can be identified.

Dead letter queues are just queues that are used where data quality or corrupt messages are detected. In cases where event formats evolve, the dead letter queue might be used in back testing to understand compatibility issues.

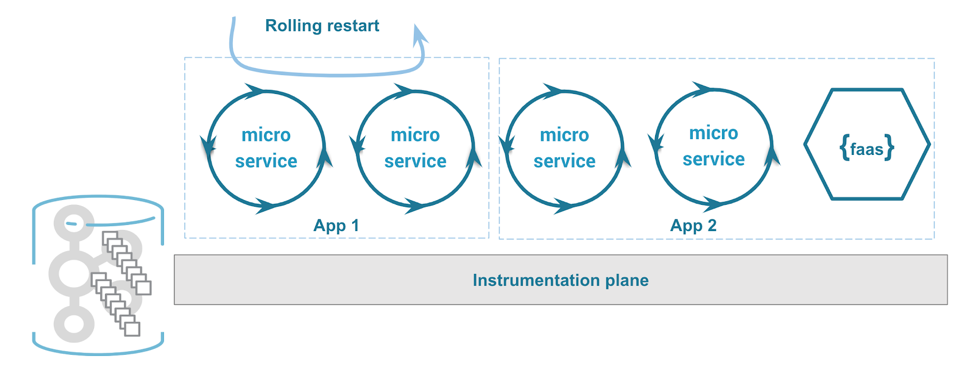

3. Control: Offline and rolling restart

Restarting stream processing microservices

Offline

Streaming apps tend to run continuously. It is critical that events are not missed, and that any stateful operations are resumed without compromising the output stream. Event streaming platforms support the ability to allow consumers to be turned off while the producer still generates messages; they are stored in the log. Upon resuming processing responsibility, the consumer’s process will pick up from where it left off. Stateful operations will also be resumed using the event sourcing model, and state will be pushed into the changelog streams.

The appealing aspect of the event streaming platform is that not only are all streams replicated across multiple locations on the backend broker infrastructure but also that all paths of failure and accuracy are catered for. Offline resilience means that replacement containers can be spun up in a new location with a new application version, and they will simply resume processing.

Rolling restart

Maintenance and operational requirements mean that the applications will inevitably be redeployed and updated. In a 24×7 environment, we leverage the event streaming platform’s consumer group protocol. This protocol ensures that members (consumers) who join and leave the group are tracked and that partitions within a stream will be redirected or rebalanced amongst the consumers as the population changes.

As mentioned previously, stateful operations are also persisted as streams at the partition or event-key level. Flexing consumers up and down, or cycling through a set of consumers on a controlled fashion like a Kubernetes operator means that rolling restart and elastic scaling are supported natively. As in the offline scenarios, the new consumer processors simply event source the related state and carry on processing.

It’s a wrap

Being event first

Being event first or event driven is about recognizing the value of events. It’s about going back to first principles, challenging every preconceived idea of how to build distributed systems. Being event first means we change our methodology to an interplay between modeling real world events as DDD, modeling events to capture those use cases and implementing the dataflow of those events for individual use cases. We also develop our monitoring and instrumentation as part of the implementation in a different event plane.

All of these elements compound upon each other with the repeated notion that the event captures a fact, a series of related events is a stream and that a stream tells a story. This is how we think about system design and architecture.

Streams capture events; a series of events capture behavior; they tell a story

Microservice frameworks are also replaced by using the event streaming platform. For years we have been consumed by various microservice frameworks and trappings of the event-command pattern. The event streaming platform solves many first-class concerns like event routing, service discovery, event sourcing, persistence and elasticity. You, as the developer, choose how to run your stream processing microservices. The streams of data flowing into and out of your microservice as well as the internal state are persisted into Kafka.

You don’t need yet another microservice framework when you use Kafka as an event streaming platform

Data evolution

Another benefit of the event streaming systems is that we can continuously extend the functionality. We can add new processors to extract different sets of intelligence stored within the event streaming patterns. This might be backtesting ad placement, driving and calibrating machine learning, identifying user behavior by geography or even tracking and identifying malicious users (HammerSnipe/auction stealing).

By storing only the events and never the commands, we have a wealth of capability that not only allows the system to be refined, extended and proven but also supports evolutionary change. As the domain or requirements change over time the platform can support the evolution of the events where new fields are added, stream processors might be updated or scaled and the architecture might change the event stream, which brings us nicely to the future state where we see streaming in the cloud.

The future of programming

Evolutionary architectures represent the next generation of thinking about cloud. The ability to compose data-driven, reactive architectures that leverage FaaS and elastic stream processing while pushing down infrastructure concerns is the journey we are on.

There are many facets to this journey, but this story is one which will take time to unfurl and become clear. We have seen many architecture revolutions in the past (e.g., big data and NoSQL), but it’s only when the principles of being event first are correctly applied to the data platform do the qualities of evolvability become attainable. Only then does it become possible for data and logic to change independently without compromising the future runtime.

We have now baked into our ideology that events are the future. Making this a reality is fun, but we are on a journey, one which will unfold as we continue to discover renewed value of going back to first principles of distributed computing.

Interested in more?

Stay tuned for more posts on this topic, including the next in the series which focuses on serverless: Part 3: The Affinity Between Events, Streams and Serverless, and part 4, where I start building a solution architecture for the payment system from the ground up and map it onto the event streaming platform and the Kafka architecture. I’ll provide a deep dive on patterns for payment processing, instrumentation and flow control as well. I also discuss the future of serverless and streaming with Tim Berglund in episode 18 of the Streaming Audio podcast.

To learn more about event-driven systems, design and concepts, I highly recommend Martin Kleppmann’s Designing Data-Intensive Applications and Ben Stopford’s book Designing Event-Driven Systems.

If you’d like to know more, you can download the Confluent Platform, the leading distribution of Apache Kafka.

Other articles in this series

このブログ記事は気に入りましたか?今すぐ共有

Confluent ブログの登録

Unlocking Data Insights with Confluent Tableflow: Querying Apache Iceberg™️ Tables with Jupyter Notebooks

This blog explores how to integrate Confluent Tableflow with Trino and use Jupyter Notebooks to query Apache Iceberg tables. Learn how to set up Kafka topics, enable Tableflow, run Trino with Docker, connect via the REST catalog, and visualize data using Pandas. Unlock real-time and historical an...

Shifting Left: How Data Contracts Underpin People, Processes, and Technology

Explore how data contracts enable a shift left in data management making data reliable, real-time, and reusable while reducing inefficiencies, and unlocking AI and ML opportunities. Dive into team dynamics, data products, and how the data streaming platform helps implement this shift.