[Virtual Event] GenAI Streamposium: Learn to Build & Scale Real-Time GenAI Apps | Register Now

Elastic Scaling in the Streams API in Kafka

This blog post is the first in a series about the Streams API of Apache Kafka, the new stream processing library of the Apache Kafka project, which was introduced in Kafka v0.10.

Current blog posts in the Kafka Streams series:

- Elastic Scaling in the Streams API in Kafka (this post)

- Secure Stream Processing with the Streams API in Kafka

- Data Reprocessing with the Streams API in Kafka: Resetting a Streams Application

In this post we are looking at the elasticity and scalability of the Streams API. Once you have implemented your stream processing application using the Streams API, you might have the following questions regarding its deployment and operation so that you can put it into production:

- Question 1 (adding capacity): If I need more processing capacity for my stream processing application, how can I scale out or “expand” my application?

- Question 2 (removing capacity): If I need less processing capacity for my stream processing application, how can I “shrink” my application?

Let’s start with two quick answers to these questions:

- Answer 1 (adding capacity): To scale out, you simply start another instance of your stream processing application, e.g. on another machine. The instances of your application will become aware of each other and automatically begin to share the processing work.

- Answer 2 (removing capacity): Simply stop one or more running instances of your stream processing application, e.g. shut down 2 of 4 running instances. The remaining instances of your application will become aware that other instances were stopped and automatically take over the processing work of the stopped instances.

We can now walk through the answers in further detail.

First, what do we mean by “starting another instance of your stream processing application”? A stream processing application that uses the Kafka Streams library is a normal Java application. Whenever you are running the application — e.g. via the java command — the corresponding JVM process is considered an “instance” of your application. So “running another instance” of the application simply means to launch the same application again (resulting in another JVM process), which you’d typically do on a different machine. The various instances of your application can leverage all the capacity that is available to their respective JVM processes (minus the capacity that any non-Kafka-Streams part of your application may be using). This explains why running additional instances will grant your application additional processing capacity. The exact capacity you will be adding by running a new instance depends of course on the environment in which the new instance runs: available CPU cores, available main memory and Java heap space, local storage, network bandwidth, and so on. Similarly, if you stop any of the running instances of your application, then you are removing and freeing up the respective processing capacity.

Second, because instances may come and go dynamically, how do the application instances figure out how to 1. split processing work when new instances were added or 2. take over processing work when existing instances were removed? The answer is that the Streams API leverages existing functionality in Kafka, notably its group management functionality. This group management, which is built right into the Kafka wire protocol, is the foundation that enables the elasticity of your Streams API applications: members of a group will coordinate and collaborate jointly on the consumption and processing of data in Kafka. In a nutshell, running instances of your application will automatically become aware of new instances joining the group, and will split the work with them; and vice versa, if any running instances are leaving the group (e.g. because they were stopped or they failed), then the remaining instances will become aware of that, too, and will take over their work. More specifically, when you are launching instances of your Streams API based application, these instances will share the same Kafka consumer group id. The group.id is a setting of Kafka’s consumer configuration, and for a Streams API based application this consumer group id is derived from the application.id setting in the Kafka Streams configuration.

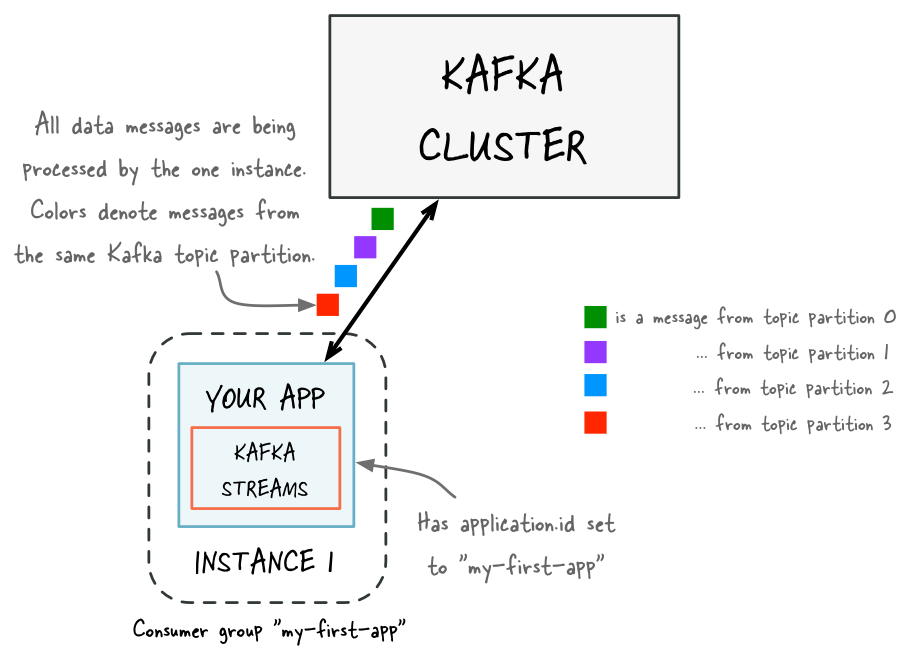

Figure 1: Before adding capacity, only a single instance of your Kafka Streams application is running. At this point the corresponding “consumer group” of your application contains only a single member (this instance). All data is being read and processed by this single instance.

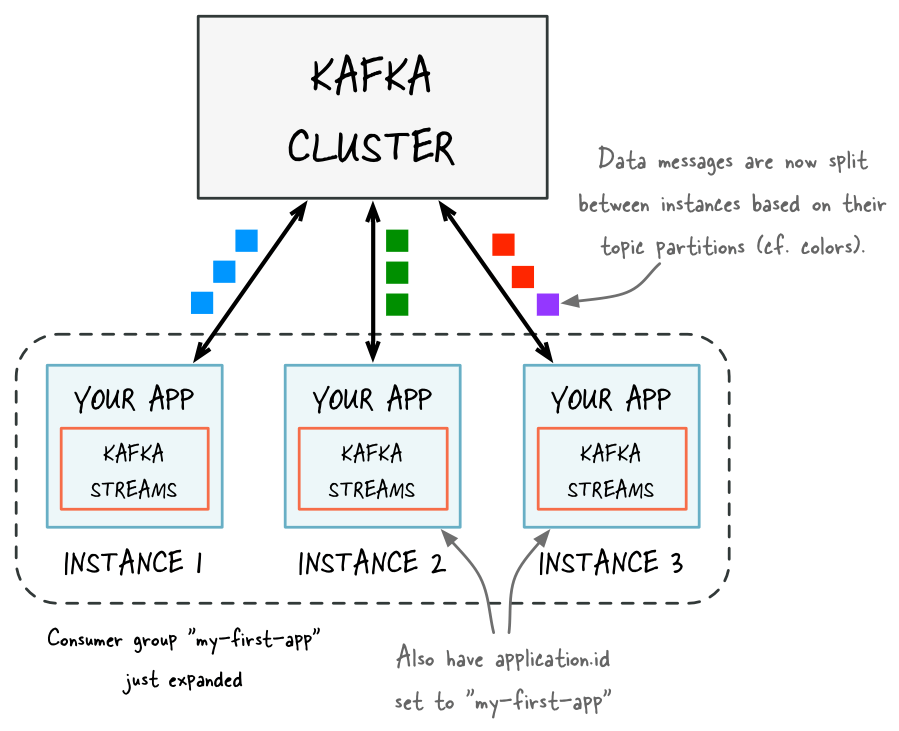

Figure 1: Before adding capacity, only a single instance of your Kafka Streams application is running. At this point the corresponding “consumer group” of your application contains only a single member (this instance). All data is being read and processed by this single instance. Figure 2: After adding capacity, two additional instances of your Streams API application are running, and they have automatically joined the application’s consumer group for a total of three current members. These three instances are automatically splitting the processing work between each other. The splitting is based on the Kafka topic partitions from which data is being read.

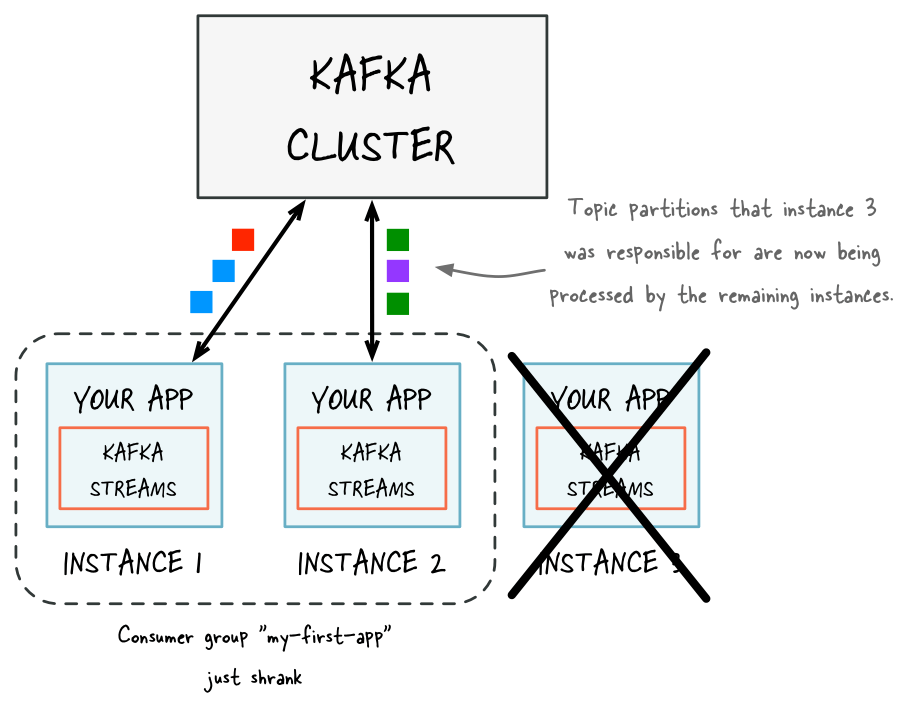

Figure 2: After adding capacity, two additional instances of your Streams API application are running, and they have automatically joined the application’s consumer group for a total of three current members. These three instances are automatically splitting the processing work between each other. The splitting is based on the Kafka topic partitions from which data is being read. Figure 3: If one of the application instances is stopped (e.g. intentional reduction of capacity, maintenance, machine failure), it will automatically leave the application’s consumer group, which causes the remaining instances to automatically take over the stopped instance’s processing work.

Figure 3: If one of the application instances is stopped (e.g. intentional reduction of capacity, maintenance, machine failure), it will automatically leave the application’s consumer group, which causes the remaining instances to automatically take over the stopped instance’s processing work.

That being said, the Streams API must take care of some additional aspects to make your application elastic. For example, the Streams API in Kafka allows for stateful stream processing operations such as aggregations, joins, or windowing. Here it is important that any such state is managed in a fault-tolerant way to safeguard against failures such as machine crashes.The details are beyond the scope of this blog post, but we have covered this information in the Streams API documentation about state and fault tolerance. The result is that a Streams API application is elastic and can scale dynamically during runtime, and can do so without any downtime or data loss. This means that, unlike other stream processing technologies, with the Streams API you do not have to completely stop your application, recompile/reconfigure, and then restart. This is great not just for intentionally adding or removing processing capacity, but also for being resilient in the face of failures (e.g. machine crashes, network outages) and for allowing maintenance work (e.g. rolling upgrades).

Third, how many instances can or should you run for your application? Is there an upper limit for the number of instances and, similarly, for the parallelism of your application? In a nutshell, the parallelism of a Streams API application — similar to the parallelism of Kafka — is primarily determined by the number of partitions of the input topic(s) from which your application is reading. For example, if your application reads from a single topic that has 10 partitions, then you can run up to 10 instances of your applications (note that you can run further instances but these will be idle). In summary, the number of topic partitions is the upper limit for the parallelism of your Streams API application and thus for the number of running instances of your application. Note: A scaling/parallelism caveat here is that the balance of the processing work between application instances depends on how well data messages are balanced between partitions.

Fourth, through which mechanism are instances of your application being started or stopped? Is there a resource manager or scheduler included in Kafka or in the Streams API? The answer is No — Kafka Streams is a library, neither a framework nor yet another “processing cluster” tool. By design and on purpose, there is no resource manager or scheduler included in the Streams API in Kafka. This may sound counter-intuitive at first, so let me elaborate. In the Streams API, we chose to leave the decision of how to deploy (start, stop, etc.) up to you because in most environments, you have already made this decision for other applications and systems, and why should stream processing applications require a different technology stack than the rest of your infrastructure? This means you can opt to start and stop instances manually (very convenient for quick prototyping or iterative development), you can use deployment tools such as Puppet or Ansible, or resource/cluster managers such as Mesos, YARN, or Kubernetes (great for production). The net effect is that, using the Streams API in Kafka, you can integrate your stream processing applications much more easily into your existing infrastructure and organizational processes.

Conclusion

In summary, the Streams API in Kafka makes your stream processing applications elastic and scalable. And all you need to do is to start or stop instances of your application as needed!

If you have enjoyed this article, you might want to continue with the following resources to learn more about Apache Kafka’s Streams API:

- Get started with the Kafka Streams API to build your own real-time applications and microservices.

- Walk through our Confluent tutorial for the Kafka Streams API with Docker and play with our Confluent demo applications.

Avez-vous aimé cet article de blog ? Partagez-le !

Abonnez-vous au blog Confluent

Stop Treating Your LLM Like a Database

GenAI thrives on real-time contextual data: In a modern system, LLMs should be designed to engage, synthesize, and contribute, rather than to simply serve as queryable data stores.

Generative AI Meets Data Streaming (Part III) – Scaling AI in Real Time: Data Streaming and Event-Driven Architecture

In this final part of the blog series, we bring it all together by exploring data streaming platforms (DSPs), event-driven architecture (EDA), and real-time data processing to scale AI-powered solutions across your organization.