Ahorra un 25 % (o incluso más) en tus costes de Kafka | Acepta el reto del ahorro con Kafka de Confluent

How PushOwl Uses ksqlDB to Scale Their Analytics and Reporting Use Cases

Using a declarative SQL-like interface, ksqlDB makes it easy to integrate event streaming applications into any tech stack. This article illustrates how ksqlDB was added to PushOwl’s Python tech stack, describes an actual business use case that was solved, and walks through our journey of using various solutions before adding Apache Kafka® and ksqlDB to our toolkit.

Simplifying e-commerce using web push notifications

PushOwl is a B2B, SaaS solution for e-commerce marketing that integrates the functionality of collecting web push subscribers and sending web push notifications to those subscribers on any website. PushOwl simplifies the way e-commerce entrepreneurs around the world communicate with their customers via web push notifications. Currently, PushOwl powers 22,000+ e-commerce businesses worldwide and is the #1 web push notification tool on the Shopify platform.

Some of the terminologies that will be used in this article include:

- Merchant: PushOwl’s customers, who are e-commerce site owners or admins.

- Subscriber: A web push notification subscriber on a merchant’s website. PushOwl prompts visitors on the merchant’s website to subscribe to web push notifications. Once they click “Allow” on that prompt, the visitor is converted to a subscriber.

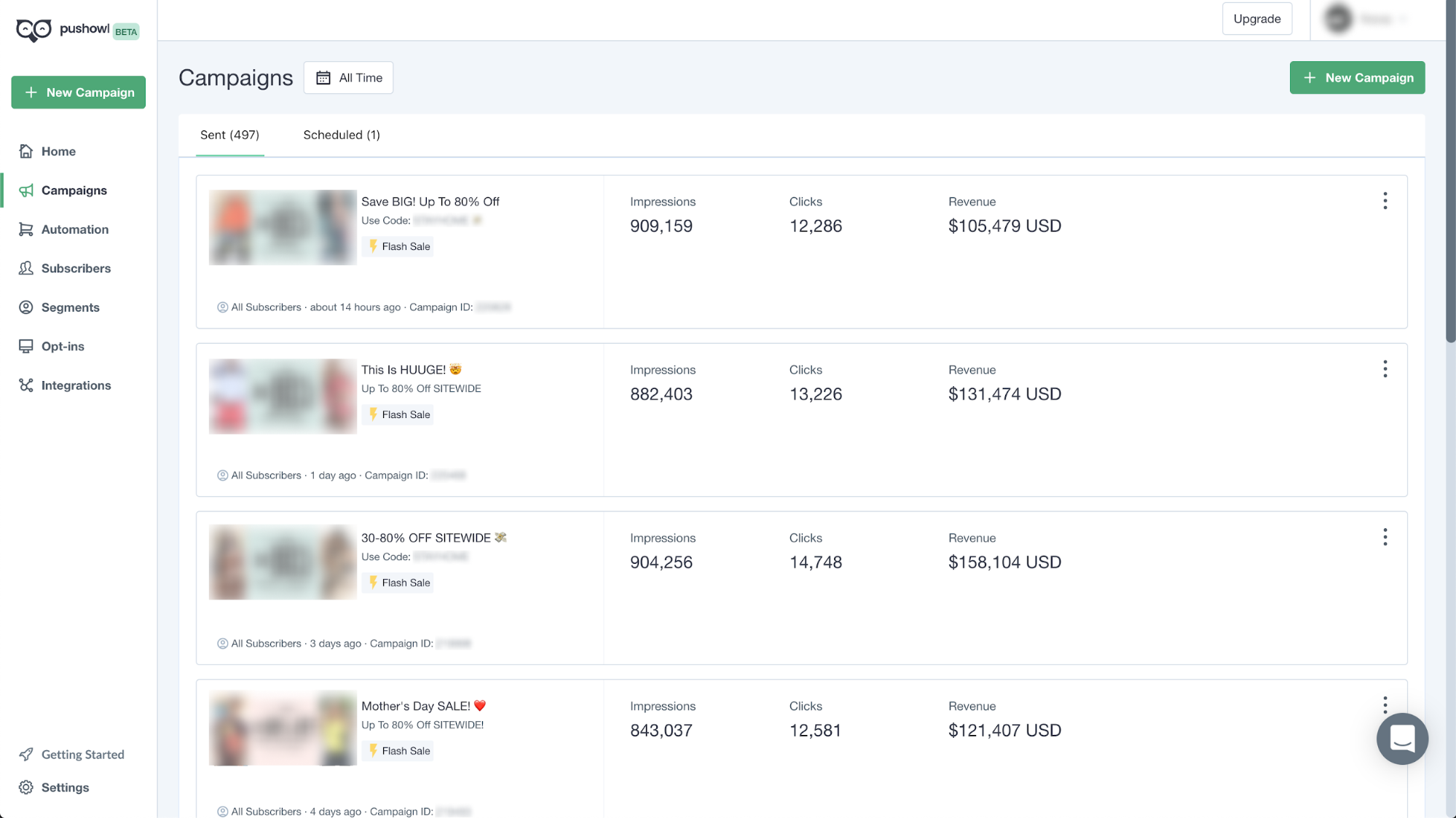

PushOwl provides a dashboard to the merchants, where they can see the performance of their marketing campaigns. As with any good marketing tool, PushOwl provides meaningful information related to each campaign sent by the merchant. Some of these metrics include the number of impressions (push notifications delivered successfully to the subscribers), the number of clicks on those push notifications, and how much revenue has been generated from the push notifications sent by that campaign. These metrics help merchants understand how their campaigns are performing.

PushOwl dashboard showing performance of the campaigns sent by the merchant

PushOwl dashboard showing performance of the campaigns sent by the merchant

PushOwl needs to store the push notification payloads for the auditing and debugging process. A typical payload is approximately 1 KB in size. PushOwl sends close to 8 million web push notifications every day, which can peak up to 5x during holiday sales.

The following are two challenges PushOwl needed to solve:

- Storage and retrieval of push notifications on demand

- Generation of campaign reports that merchants can easily access via their PushOwl dashboard

How would you go about solving these two problems within a traditional web framework?

The remainder of this blog post details two of the solutions that PushOwl implemented to address these challenges, describes why some of them did not work and subsequently, why ksqlDB was ultimately chosen as the final solution.

Solution #1: Querying database for campaign reports

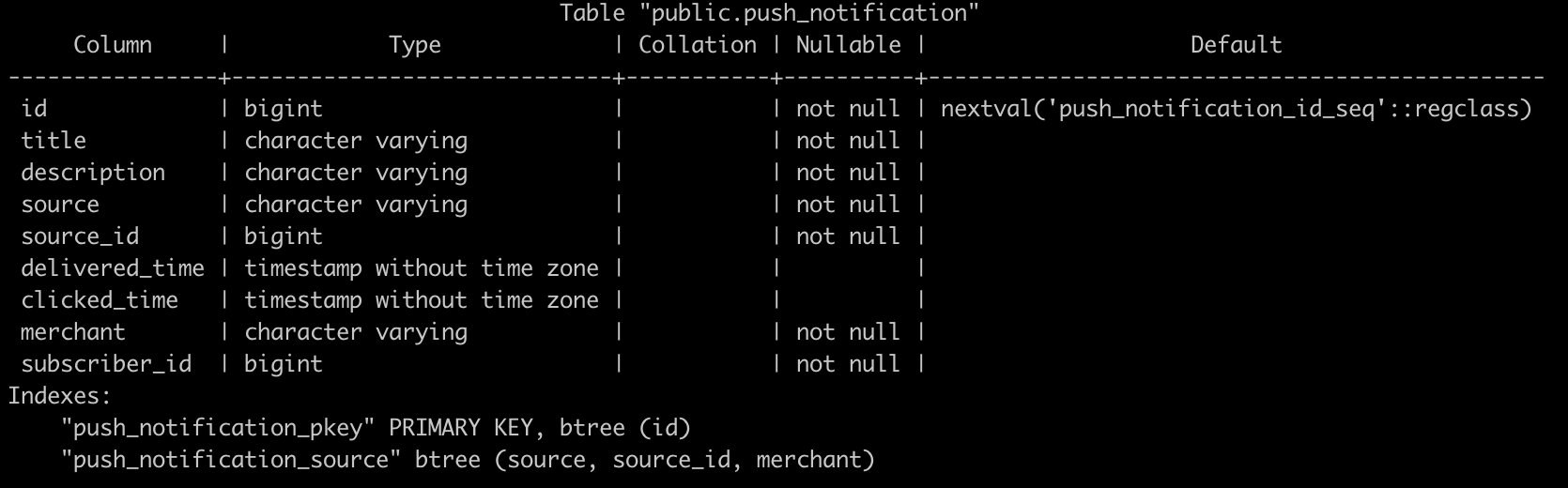

In our first solution, a push_notification table was created in PushOwl’s PostgreSQL database and was designed to store all push notifications that were sent. The table schema looked like the following:

Push notification table schema in the PostgreSQL database

Push notification table schema in the PostgreSQL database

This was designed to listen to the delivery and click pings from PushOwl’s service workers running in the browsers of subscribers, and would then update the push_notification table with a delivery and click timestamp for a particular push notification. The delivery and click pings contain PushNotificationId in their payload.

The following SQL query updates the delivered_time column for a given PushNotificationId:

UPDATE

push_notification

SET

delivered_time=now()

WHERE

id=<PushNotificationId>;

Similarly, the following SQL query updates the clicked_time column for a push notification:

UPDATE

push_notification

SET

clicked_time=now()

WHERE

id=<PushNotificationId>;

Once all impression and click data was in the push_notification table, querying for the performance of a campaign for a merchant my-cool-shop required a simple SQL query:

SELECT

count(delivered_time) AS impressions,

count(clicked_time) AS clicks,

source_id AS campaign_id

FROM

push_notification

WHERE

source = 'campaign'

AND merchant = 'my-cool-shop'

GROUP BY source_id;

This system served well for PushOwl for the first few months. Whenever a merchant opened their campaign reporting dashboard, this query would run in the PushOwl web server. The GET API call would be blocked until the query had been evaluated.

Unfortunately, as the table size increased, the SQL query execution began to slow down. The SQL query would run every time the merchant refreshed their campaign reporting dashboard, and slower queries meant slower page load, resulting in poor user experiences.

The next section explains how PushOwl solved the slow API problems by transitioning to a second solution, which at the time, only involved approximately half of the volume PushOwl manages today.

Solution #2: Materialising the campaign report in the database

PushOwl needed a way to solve the slow API problem, which surfaced due to slow SQL query execution. The first step was to store the aggregated campaign report from the push_notification table to the campaign table for every campaign sent within the last 30 days. Since web push notifications have a fixed time to live, no new pings were received after 28 days.

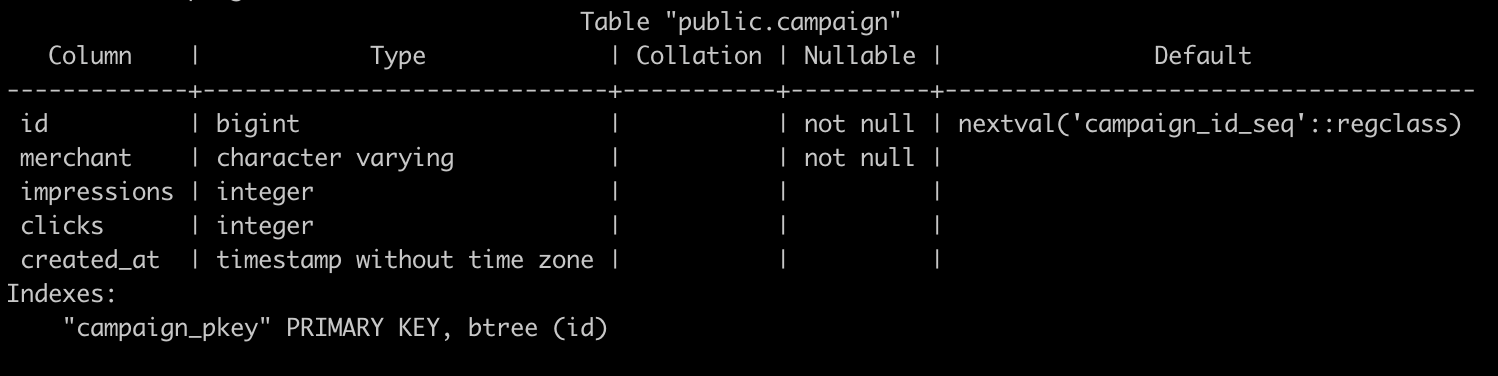

Here’s the structure of the campaign table:

Campaign table schema in the PostgreSQL database

Campaign table schema in the PostgreSQL database

The query below was used to aggregate and store campaign performance in the campaign table. This would run every hour using a cron job.

WITH campaigns_in_last_30_days AS (

SELECT

id

FROM

campaign

WHERE

created_at >= now() - interval '30 days'

), campaign_report AS (

SELECT

count(delivered_time) AS impressions,

count(clicked_time) AS clicks,

source_id AS campaign_id

FROM

push_notification

WHERE

source = 'campaign'

AND source_id IN (SELECT id FROM campaigns_in_last_30_days)

GROUP BY

source_id

) UPDATE

campaign

SET

clicks = campaign_report.clicks,

impressions = campaign_report.impressions

FROM

campaign_report

WHERE

campaign_report.campaign_id = campaign.id;

Whenever a merchant visited the dashboard for a campaign report, the campaign table was queried instead of the push_notification table. The results were identical to the results that would have been received by querying the push_notification table.

SELECT

id as campaign_id,

impressions,

clicks

FROM

campaign

WHERE

merchant='my-cool-shop';

Similar to the first solution, this approach could not scale. The data in the push_notification table was increasing at the rate of 10 GB per day, and index size was increasing at the rate of 1 GB per day. Due to the ever-increasing index size of the push_notification table, there was a lot of thrashing in the database queries that started to affect other queries as well, causing slow dashboard loads and a myriad of other performance problems.

Enter event streaming

Event streaming, and ksqlDB in particular, was able to solve PushOwl’s storage and access challenges. Publishing to Kafka was fairly straightforward since all the heavy lifting is done by the Kafka client library, but we could not settle on a stream aggregation framework at first.

Apache Spark (structured streaming) was the obvious candidate, since we could use PySpark for the event aggregations. But at the time of implementing the solution, PySpark did not support reading and writing data in Avro format. We also had to write all the data frame transformations, which was a bit hard to maintain.

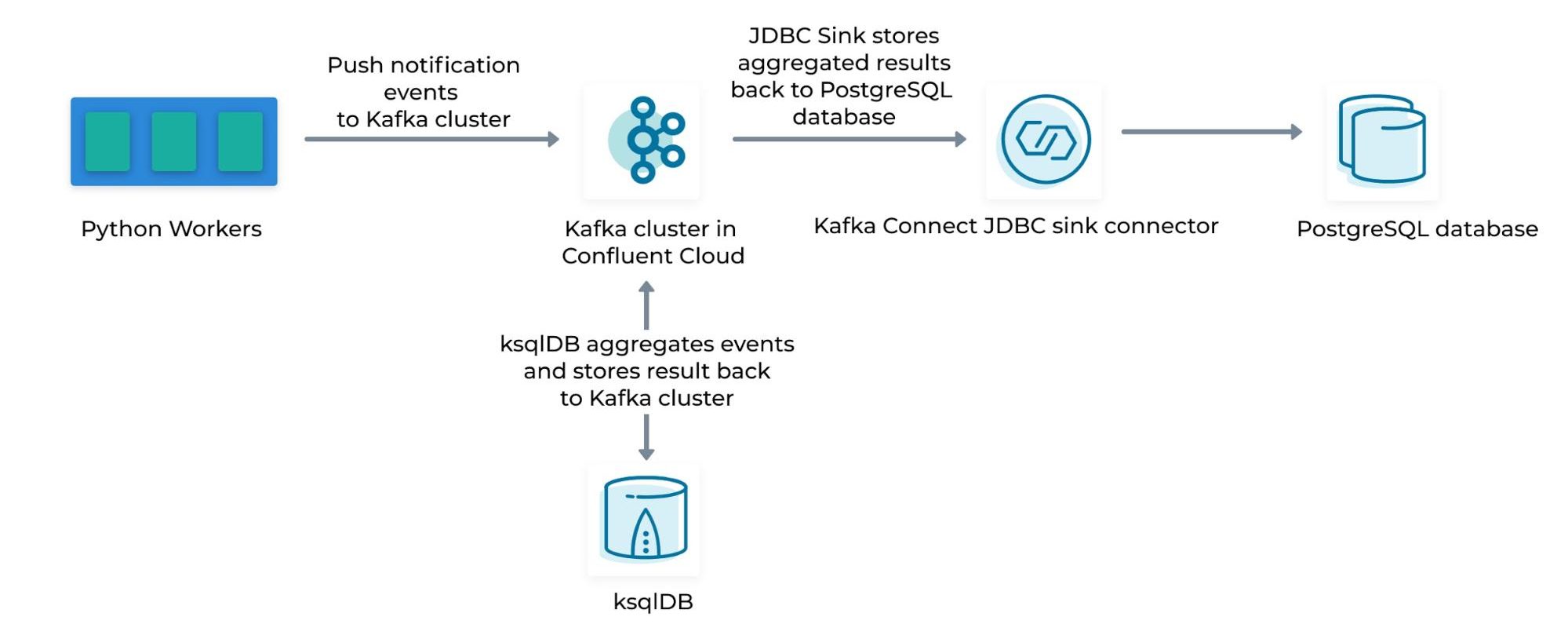

When we stumbled onto Confluent Cloud and ksqlDB, it was super easy to integrate event streaming applications into our tech stack. ksqlDB creates event streaming applications in a declarative way, which means we did not have to write any step-by-step procedures or code. We achieved stream aggregation using the confluent_kafka Python package, Kafka Connect JDBC sink connector, Kafka Connect S3 sink connector, and ksqlDB.

This is what the architecture looked like:

Dataflow illustrating: 1) Publishing of events to Kafka from our Python workers 2) Event stream aggregation using a ksqlDB cluster 3) Storing of aggregated event streams from Kafka back to our PostgreSQL database using the Kafka Connect JDBC Connector

Dataflow illustrating: 1) Publishing of events to Kafka from our Python workers 2) Event stream aggregation using a ksqlDB cluster 3) Storing of aggregated event streams from Kafka back to our PostgreSQL database using the Kafka Connect JDBC Connector

Dataflow illustrating: 1) Publishing of events to Kafka from our Python workers 2) Storing those events to Amazon S3 using the Kafka Connect S3 Connector

Dataflow illustrating: 1) Publishing of events to Kafka from our Python workers 2) Storing those events to Amazon S3 using the Kafka Connect S3 Connector

The next section illustrates the ksqlDB query that was used to finally solve both use cases.

Code examples

Let’s now take a look at the dataflow from the Python workers to Kafka along with some working code examples, from which you can get ideas to build your own solution.

First, we created an account on Confluent Cloud and add a cluster. We created separate producers for push notification dispatch and push notification ping events in our Python workers. We also created separate topics in the Kafka cluster for publishing those events.

import json from confluent_kafka import avro from confluent_kafka.avro import AvroProducer

push_notification_dispatch_schema_json = { "namespace": "com.pushowl", "type": "record", "name": "push_notification_dispatch", "fields": [ { "name": "title", "type": "string" }, { "name": "description", "type": ["string", "null"] }, { "name": "source", "type": "string" }, { "name": "source_id", "type": "long" }, { "name": "merchant", "type": "string" }, { "name": "subscriber_id", "type": "long" }] }

push_notification_ping_schema_json = { "namespace": "com.pushowl", "type": "record", "name": "push_notification_ping", "fields": [ { "name": "merchant", "type": "string" }, { "name": "source", "type": "string" }, { "name": "source_id", "type": "long" }, { "name": "subscriber_id", "type": "long" }, { "name": "delivered_time", "type": [ "null", "string" ] }, { "name": "clicked_time", "type": [ "null", "string" ] } ] }

common_config = { 'bootstrap.servers': 'CLUSTER_ENDPOINT', 'sasl.mechanisms': 'PLAIN', 'security.protocol': 'SASL_SSL', 'sasl.username': 'CLUSTER_ACCESS_KEY_ID', 'sasl.password': 'CLUSTER_ACCESS_KEY_SECRET', 'enable.idempotence': True, 'schema.registry.url': 'SCHEMA_REGISTERY_ENDPOINT', 'schema.registry.basic.auth.credentials.source': 'SCHEMA_REGISTRY_ACCESS_KEY_ID', 'schema.registry.basic.auth.user.info': 'SCHEMA_REGISTRY_ACCESS_KEY_SECRET' }

PushHelper.DISPATCH_PRODUCER = AvroProducer(dict( common_config, **{'client.id': 'push_notification_dispatch'} ), default_value_schema=avro.loads(json.dumps(push_notification_dispatch_schema_json)))

PushHelper.PING_PRODUCER = AvroProducer(dict( common_config, **{'client.id': 'push_notification_ping'} ), default_value_schema=avro.loads(json.dumps(push_notification_ping_schema_json)))

After initialising both producers in the workers, we started publishing events using those producers to the Kafka cluster.

pn_dispatch_topic = 'pushnotification-dispatch' pn_ping_topic = 'pushnotification-ping'

Here is how we started publishing push notifications dispatch events:

PushHelper.DISPATCH_PRODUCER.produce(

topic=pn_dispatch_topic,

value={

"title": push_notification.title,

"description": push_notification.description,

"source": push_notification.source or 'None', # source can not be None

"source_id": push_notification.source_id or -1, # source_id can not be None

"merchant": push_notification.merchant,

"subscriber_id": push_notification.subscriber_id

}

)

Similarly, we started publishing push notifications delivery and click events

PushHelper.PING_PRODUCER.produce(

topic=pn_ping_topic,

value={

"source": ping_event.source or 'None', # source can not be None

"source_id": ping_event.source_id or -1, # source_id can not be None

"merchant": ping_event.merchant,

"subscriber_id": ping_event.subscriber_id,

"delivered_time": ping_event.delivered_time.__str__(),

"subscriber_id": ping_event.subscriber_id

}

)

PushHelper.PING_PRODUCER.produce(

topic=pn_ping_topic,

value={

"source": ping_event.source or 'None', # source can not be None

"source_id": ping_event.source_id or -1, # source_id can not be None

"merchant": ping_event.merchant,

"subscriber_id": ping_event.subscriber_id,

"clicked_time": ping_event.clicked_time.__str__(),

"subscriber_id": ping_event.subscriber_id

}

)

Now that the delivery and click ping data was getting streamed in the Kafka topic, we added a table in the ksqlDB cluster. ksqlDB would ingest data from the pushnotification-ping topic and start streaming the aggregated result back to the campaign-reporting topic in the same Kafka cluster.

CREATE TABLE `campaign-reporting` WITH (

KAFKA_TOPIC='campaign-reporting',

PARTITIONS=12,

REPLICAS=3

) AS SELECT

COUNT(`pushnotification-ping`.DELIVERED_TIME) `impressions`,

COUNT(`pushnotification-ping`.CLICKED_TIME) `clicks`,

`pushnotification-ping`.SOURCE_ID `id`,

FROM

`pushnotification-ping` `pushnotification-ping`

WHERE

`pushnotification-ping`.SOURCE = 'campaign'

GROUP BY

`pushnotification-ping`.SOURCE_ID

EMIT CHANGES;

Voila! Just like magic.

The campaign-reporting topic was created in the same Kafka cluster. We now needed to store the aggregated results back to the PostgreSQL database so that merchants could access it using their dashboard. To do this, we used the Kafka Connect JDBC Sink Connector.

"""Configures a Kafka Sink Connector for Postgres""" import dj_database_url import requests import structlog

from common.config import KAFKA_CONNECT_URL

logger = structlog.get_logger(__name__)

db_config = dj_database_url.config()

def configure_connector(): """Starts and configures the Kafka Connect connector"""

connector_name = 'CAMPAIGN_REPORT_TO_DB' logger.info('creating or updating kafka connect connector', connector_name=connector_name)

connector_config = { "connector.class": "io.confluent.connect.jdbc.JdbcSinkConnector", "connection.url": f'jdbc:postgresql://{db_config["HOST"]}:5432/{db_config["NAME"]}?user={db_config["USER"]}&password={db_config["PASSWORD"]}&sslmode=require', "key.converter": "org.apache.kafka.connect.storage.StringConverter", "topics": "campaign-reporting", "insert.mode": "update", "pk.mode": "record_value", "pk.fields": "id", "fields.whitelist": "id,impressions,clicks", "table.name.format": "campaign" }

resp = requests.get(f"{KAFKA_CONNECT_URL}/connectors/{connector_name}") if resp.status_code == 200: endpoint = f'{KAFKA_CONNECT_URL}/connectors/{connector_name}/config' connector_exists = True else: endpoint = f'{KAFKA_CONNECT_URL}/connectors' connector_exists = False connector_config = { "name": connector_name, "config": connector_config }

if connector_exists: resp = requests.put( endpoint, headers={"Content-Type": "application/json"}, json=connector_config ) else: resp = requests.post( endpoint, headers={"Content-Type": "application/json"}, json=connector_config ) resp.raise_for_status() logger.info(f'connector {"updated" if connector_exists else "created"} successfully', response=resp.json())

After this, all the campaigns in the campaign table were updated with the number of impressions and clicks, which we could query to show on the merchant’s dashboard.

In a very similar way, we added an S3 Sink Connector for both the ping and dispatch topic to help persist those payloads for further auditing and debugging. We were easily able to slice and dice on that data using Amazon Athena.

Conclusion

ksqlDB makes it very easy to add event streaming applications into any tech stack. There are Kafka client libraries for most of the popular programming languages, which you can use to publish data to Kafka. Once the data is in Kafka, you can use the declarative interface of ksqlDB to achieve highly scalable and fault-tolerant stream aggregation use cases. A Kafka cluster in Confluent Cloud can elastically scale up to 100 MB/s, and you can always throw in more processing for the ksqlDB cluster.

This solution can easily scale to 100x of what PushOwl is doing right now. Confluent Cloud Support is also very helpful and has a swift turnaround time. I also joined the Confluent Community Slack, where the community is always eager to help one another.

A huge shoutout to all the support engineers who have helped us along the way. Feel free to reach out to me on the Confluent Community Slack if you think I can help you to better understand what we have done at PushOwl.

Thanks to Asiya Nayeem, Kavana Desai, Kushagra Gaur, and Shashank Kumar from the PushOwl team for feedback and review. Thanks to Colin Hicks from Confluent for working with me in finalising this post and to Michael Drogalis from Confluent for providing me with the opportunity to write this post. Thank you to Derek Nelson, Janine Van Poppelen, Victoria Yu, and Victoria Xia for their review. Finally, thanks to all of you for reading this post.

¿Te ha gustado esta publicación? Compártela ahora

Suscríbete al blog de Confluent

3 Strategies for Achieving Data Efficiency in Modern Organizations

The efficient management of exponentially growing data is achieved with a multipronged approach based around left-shifted (early-in-the-pipeline) governance and stream processing.

Chopped: AI Edition - Building a Meal Planner

Dinnertime with picky toddlers is chaos, so I built an AI-powered meal planner using event-driven multi-agent systems. With Kafka, Flink, and LangChain, agents handle meal planning, syncing preferences, and optimizing grocery lists. This architecture isn’t just for food, it can tackle any workflow.