[Webinar] AI-Powered Innovation with Confluent & Microsoft Azure | Register Now

Turning the database inside-out with Apache Samza

This is an edited and expanded transcript of a talk I gave at Strange Loop 2014. The video recording (embedded below) has been watched over 8,000 times. For those of you who prefer reading, I thought it would be worth writing down the talk.

Databases are global, shared, mutable state. That’s the way it has been since the 1960s, and no amount of NoSQL has changed that. However, most self-respecting developers have got rid of mutable global variables in their code long ago. So why do we tolerate databases as they are?

A more promising model, used in some systems, is to think of a database as an always-growing collection of immutable facts. You can query it at some point in time — but that’s still old, imperative style thinking. A more fruitful approach is to take the streams of facts as they come in, and functionally process them in real-time.

This talk introduces Apache Samza, a distributed stream processing framework developed at LinkedIn. At first it looks like yet another tool for computing real-time analytics, but it’s more than that. Really it’s a surreptitious attempt to take the database architecture we know, and turn it inside out.

At its core is a distributed, durable commit log, implemented by Apache Kafka. Layered on top are simple but powerful tools for joining streams and managing large amounts of data reliably.

What do we have to gain from turning the database inside out? Simpler code, better scalability, better robustness, lower latency, and more flexibility for doing interesting things with data. After this talk, you’ll see the architecture of your own applications in a new light.

This talk is about database architecture and application architecture. It’s somewhat related to an open source project I’ve been working on, called Apache Samza. I’m Martin Kleppmann, and I was until recently at LinkedIn working on Samza. At the moment I’m taking a sabbatical to write a book for O’Reilly, called Designing Data-Intensive Applications.

Let’s talk about databases. What I mean is not any particular brand of database — I don’t mind whether you’re using relational, or NoSQL, or whatever. I’m really talking about the general concept of a database, as we use it when building applications.

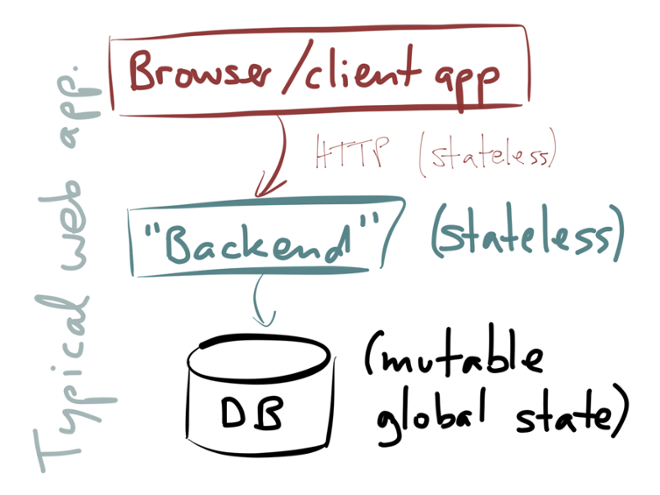

Take, for example, the stereotypical web application architecture:

You have a client, which may be a web browser or a mobile app, and that client talks to some kind of server-side system (which you may call a “backend” or whatever you like). The backend typically implements some kind of business logic, performs access control, accepts input, produces output. When the backend needs to remember something for the future, it stores that data in a database, and when it needs to look something up, it queries a database. That’s all very familiar stuff.

The way we typically build these sorts of applications is that we make the backend layer stateless. That has a lot of advantages: you can scale out the backend by just running more processes in parallel, and you can route any request to any backend instance (they are all equally well qualified to handle the request), so it’s easy to spread the load across multiple machines. Any state that is required to handle a request will be looked up from the database on each request. That also works nicely with HTTP, since HTTP is a stateless protocol.

However, the big problem with this approach is: the state has to go somewhere, and so we have to put it in the database. We are now using the database as a kind of gigantic, global, shared, mutable state. It’s like a global variable that’s shared between all your application servers. It’s exactly the kind of horrendous thing that, in shared-memory concurrency, we’ve been trying to get rid of for ages. Actors, channels, goroutines, etc. are all attempts to get away from shared-memory concurrency, avoiding the problems of locking, deadlock, concurrent modifications, race conditions, and so on.

We’re trying to get away from shared-memory concurrency, but with databases we’re still stuck with this big, shared, mutable state. So it’s worth thinking about this: if we’re trying to get rid of shared memory in our single-process application architecture, what would happen if we tried to get rid of this shared mutable state on a whole-system level? At the moment, it seems to me that the main reason why systems are still being built with mutable databases is just inertia: that’s the way we’ve building applications for decades, and we don’t really have good tools to do it differently. So, let’s think about what other possibilities we have for building stateful systems.

At the moment, it seems to me that the main reason why systems are still being built with mutable databases is just inertia: that’s the way we’ve building applications for decades, and we don’t really have good tools to do it differently. So, let’s think about what other possibilities we have for building stateful systems.

In order to try to figure out what routes we could take, I’d like to look at four different examples of things that databases currently do, and things that we do with databases. And these four examples might give us an indicator of the directions in which we could take these systems forward in future.

The first example I’d like to look at is replication. You probably know about the basics of replication: the idea is that you have a copy of the same data on multiple machines (nodes), so that you can serve reads in parallel, and so that the system keeps running if you lose a machine.

It’s the database’s job to keep those replicas in sync. A common architecture for replication is that you send your writes to one designated node (which you may call the leader, master or primary), and it’s the leader’s responsibility to ensure that the writes are copied to the other nodes (which you may call followers, slaves or standbys). There are also other ways of doing it, but leader-based replication is familiar — many systems are built that way.

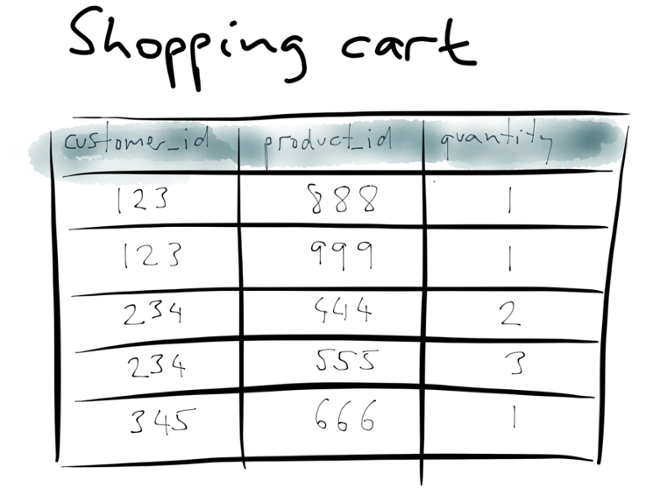

Let’s look at an example of replication to see what’s actually happening under the hood. Take a shopping cart, for instance.

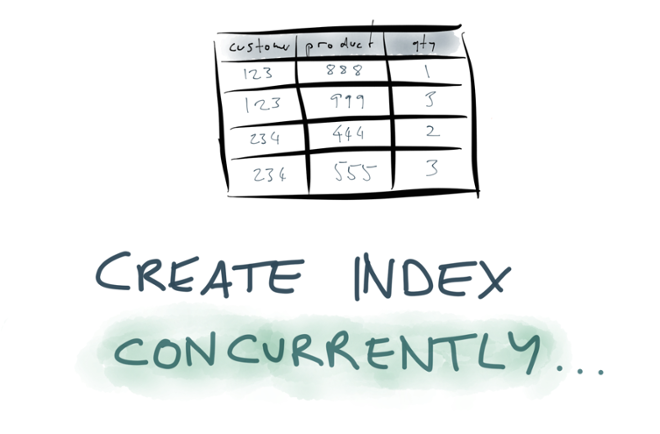

This is using a relational data model, but the same principles apply with other data models too. Say you have a table with three columns: customers, products, and quantity. Each row indicates that a particular customer has a particular quantity of a particular product in their shopping cart.

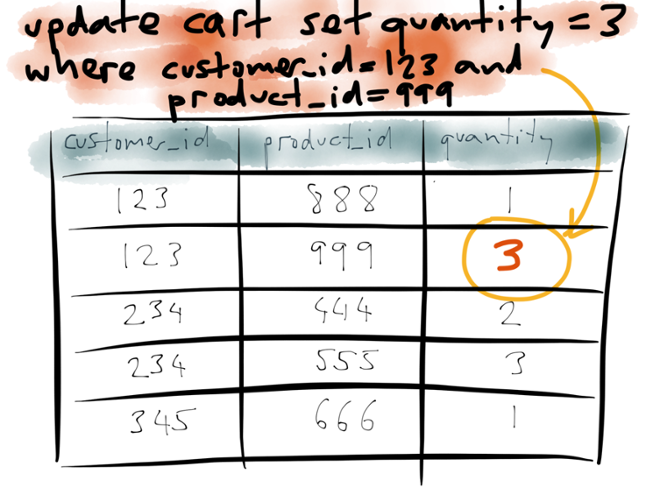

Now say customer 123 changes their mind, and instead of wanting quantity 1 of product 999, they actually want quantity 3 of that product. So they issue an update query to the database, which matches the row for customer 123 and product 999, and it changes the value of the quantity column from 1 to 3.

The result is that the database overwrites the quantity value with the new value, i.e. it applies the update in the appropriate place.

Now, I was talking about replication. What does this update do in the context of replication? Well, first of all, you send this update query to your leader, and it executes the query, figures out which rows match the condition, and applies the write locally:

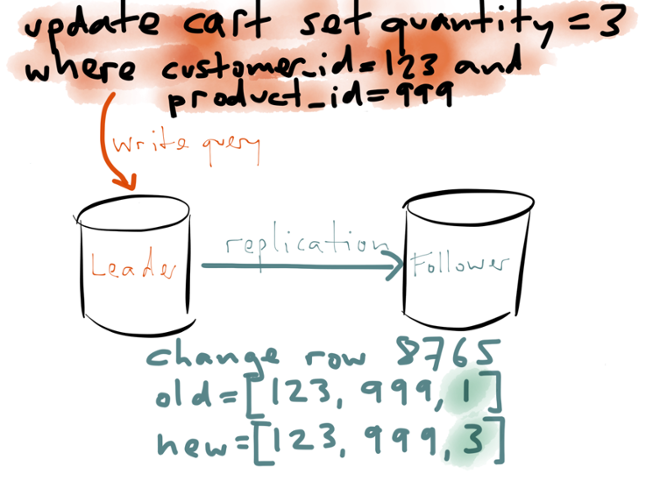

Now, how does this write get applied to the other replicas? There are several different ways how you can implement replication. One option is to send the same update query to the follower, and it executes the same statement on its own copy of the database. Another option is to ship the write-ahead log from the leader to the follower.

A third option for replication, which I’ll focus on here, is called a logical log. In this case, the leader writes out the effect that the query had — i.e. which rows were inserted, updated or deleted — like a kind of diff. For an update, like in this example, the logical log identifies the row that was changed (using a primary key or some kind of internal tuple identifier), gives the new value of that row, and perhaps also the old value.

This might seem like nothing special, but notice that something interesting has happened here:

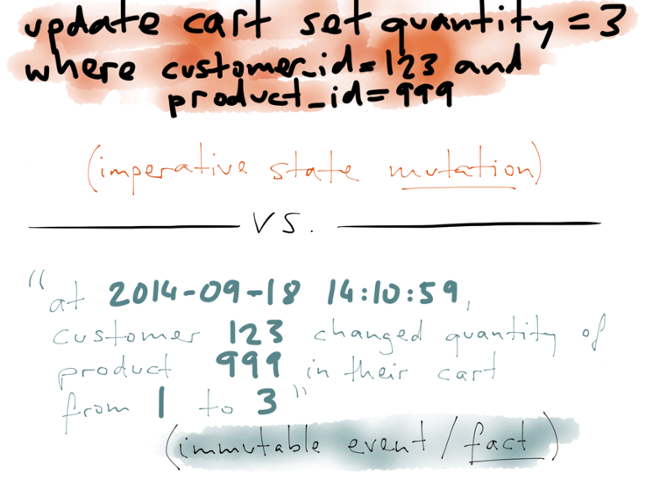

At the top we have the update statement, an imperative statement describing the state mutation. It is an instruction to the database, telling it to modify certain rows in the database that match certain conditions.

At the top we have the update statement, an imperative statement describing the state mutation. It is an instruction to the database, telling it to modify certain rows in the database that match certain conditions.

On the other hand, when the write is replicated from the leader to the follower as part of the logical log, it takes a different form: it becomes an event, stating that at a particular point in time, a particular customer changed the quantity of a particular product in their cart from 1 to 3. And this is a fact — even if the customer later removes the item from their cart, or changes the quantity again, or goes away and never comes back, that doesn’t change the fact that this state change occurred. The fact always remains true.

This distinction between an imperative modification and an immutable fact is something you may have seen in the context of event sourcing. That’s a method of database design that says you should structure all of your data as immutable facts, and it’s an interesting idea.

However, what I’m saying here is: even if you use your database in the traditional way, overwriting old state with new state, the database’s internal replication mechanism may still be translating those imperative statements into a stream of immutable events.

Hold that thought for now: I’m going to talk about some completely different things, and return to this idea later. The second one of the four things I want to talk about is secondary indexing. You’re probably familiar with secondary indexes — they are the bread and butter of relational databases. Using the shopping cart example again:

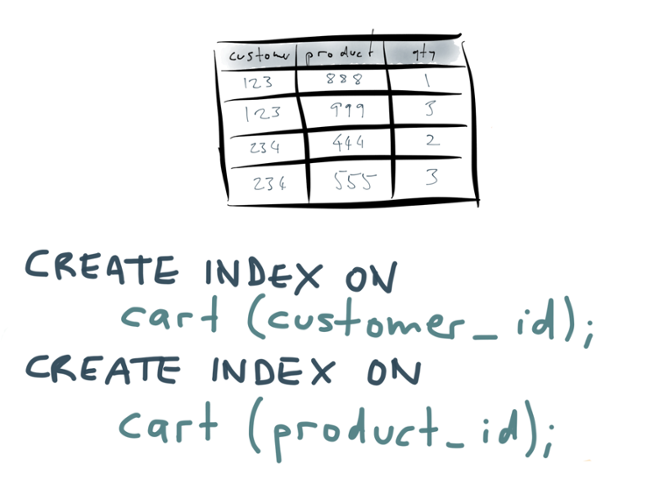

The second one of the four things I want to talk about is secondary indexing. You’re probably familiar with secondary indexes — they are the bread and butter of relational databases. Using the shopping cart example again: You have a table with different columns, and you may have several different indexes on that table in order to be able to efficiently find rows that match a particular query. For example, you may run some SQL to create two indexes: one on the customer_id column, and a separate index on the product_id column.

You have a table with different columns, and you may have several different indexes on that table in order to be able to efficiently find rows that match a particular query. For example, you may run some SQL to create two indexes: one on the customer_id column, and a separate index on the product_id column.

Using the index on customer_id you can then efficiently find all the items that a particular customer has in their cart. Using the index on product_id you can efficiently find all the carts that contain a particular product.

What does the database do when you run one of these CREATE INDEX queries?

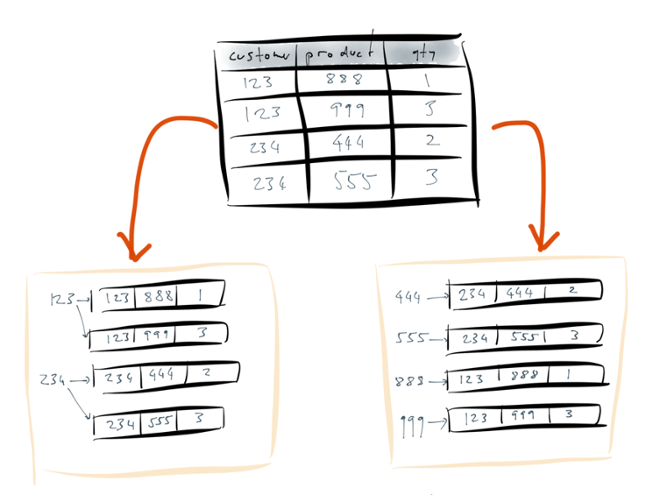

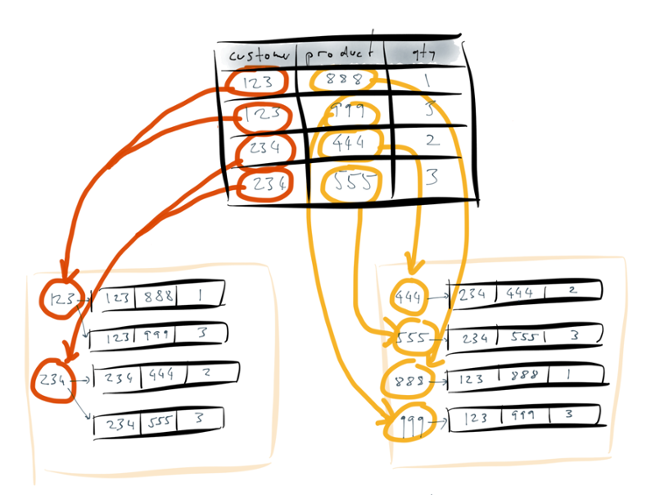

The database scans over the entire table, and it creates an auxiliary data structure for each index. An index is a data structure that represents the information in the base table in some different way. In this case, the index is a key-value-like structure: the keys are the contents of the column that you’re indexing, and the values are the rows that contain this particular key.

Put another way: to build the index for the customer_id column, the database takes all the values that appear in that column, and uses them as keys in a dictionary. A value points at all of the occurrences of that value — for example, the index entry 123 points at all of the rows which have a customer_id of 123. Similarly for the other index.

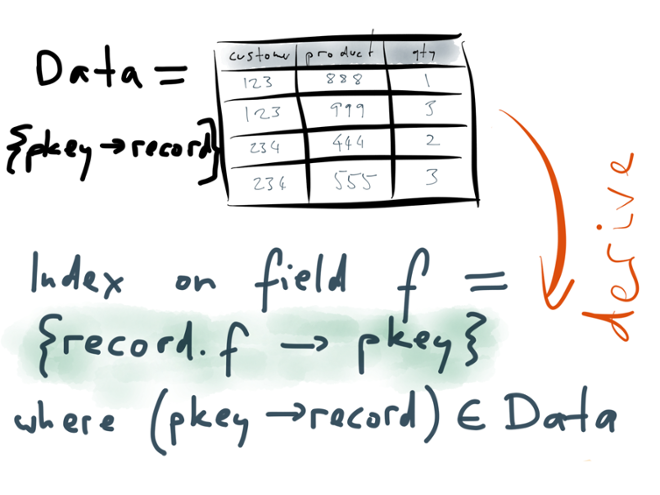

The important point here is that the process of going from the base table to the indexes is completely mechanical. You simply tell the database that you want a particular index to exist, and it goes away and builds that index for you. The index doesn’t add any new information to the database — it just represents the existing data in a different structure. (Put another way, if you drop the index, that doesn’t delete any data from your database.) It’s a redundant data structure that only exists to make certain queries faster. And that data structure can be entirely derived from the original table.

The index doesn’t add any new information to the database — it just represents the existing data in a different structure. (Put another way, if you drop the index, that doesn’t delete any data from your database.) It’s a redundant data structure that only exists to make certain queries faster. And that data structure can be entirely derived from the original table.

Creating an index is essentially a transformation which takes a database table as input, and produces an index as output. The transformation consists of going through all the rows in the table, picking out the field that you want to index, and restructuring the data so that you can look up by that field. That transformation is built into the database, so you don’t need to implement it yourself. You just tell the database that you want an index on a particular field to exist, and it does all the work of building it.

Another great thing about indexes: whenever the data in the underlying table changes, the database automatically updates the indexes to be consistent with the new data in the table. In other words, this transformation function which derives the index from the original table is not just applied once when you create the index, but applied continuously.

With many databases, these index updates are even done in a transactionally consistent way. This means that any later transactions will see the data in the index in the same state as it is in the underlying table. If a transaction aborts and rolls back, the index modifications are also rolled back. That’s a really great feature which we often don’t appreciate! What’s even better is that some databases let you build an index at the same time as continuing to process write queries. In PostgreSQL, for example, you can say CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY. On a large table, creating an index could take several hours, and on a production database you wouldn’t want to have to stop writing to the table while the index is being built. The index builder really needs to be a background process which can run while your application is simultaneously reading and writing to the database as usual.

What’s even better is that some databases let you build an index at the same time as continuing to process write queries. In PostgreSQL, for example, you can say CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY. On a large table, creating an index could take several hours, and on a production database you wouldn’t want to have to stop writing to the table while the index is being built. The index builder really needs to be a background process which can run while your application is simultaneously reading and writing to the database as usual.

The fact that databases can do this is quite impressive. After all, to build an index, the database has to scan the entire table contents, but those contents are changing at the same time as the scan is happening. The index builder is tracking a moving target. At the end, the database ends up with a transactionally consistent index, despite the fact that the data was changing concurrently.

In order to do this, the database needs to build the index from a consistent snapshot at one point in time, and also keep track of all the changes that occurred since that snapshot while the index build was in progress. That’s a really cool feature.

So far we’ve discussed two aspects of databases: replication and secondary indexing. Let’s move on to number 3: caching. What I’m talking about here is caching that is explicitly done by the application. (You also get caching happening automatically at various levels, such as the operating system’s page cache and the CPU caches, but that’s not what I’m talking about here.)

What I’m talking about here is caching that is explicitly done by the application. (You also get caching happening automatically at various levels, such as the operating system’s page cache and the CPU caches, but that’s not what I’m talking about here.)

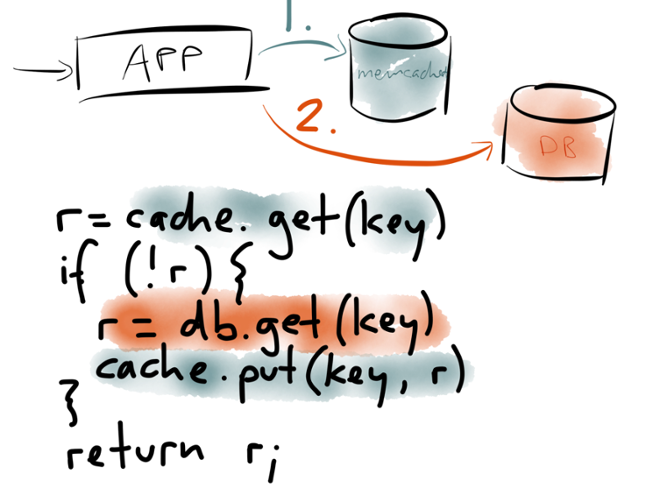

Say you have a website that becomes popular, and it becomes too expensive or too slow to hit the database for every web request, so you introduce a caching layer — often using memcached or Redis or something of that sort. And often this cache is managed in application code, which typically looks something like this:

When a request arrives at the application, you first look in a cache to see whether the data you want is already there. The cache lookup is typically by some key that describes the data you want. If the data is in the cache, you can return it straight to the client.

If the data you want isn’t in the cache, that’s a cache miss. You then go to the underlying database, and query the data that you want. On the way out, the application also writes that data to the cache, so that it’s there for the next request that needs it. The thing it writes to the cache is whatever the application would have wanted to see there in the first place. Then the application returns the data to the client.

This is a very common pattern, but there are several big problems with it.

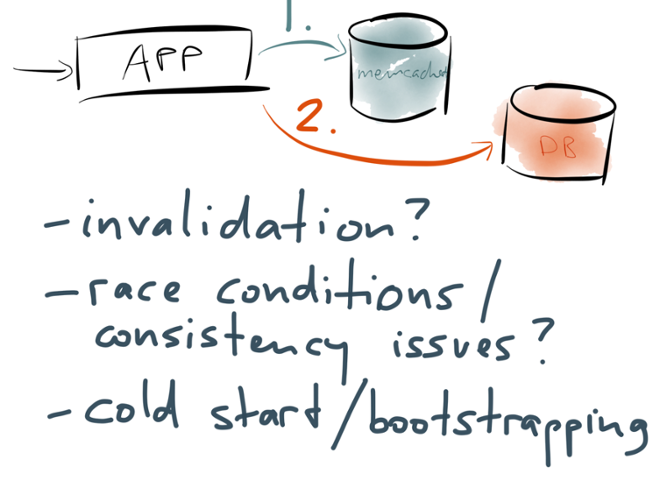

The first problem is that clichéd quote about there being only two hard problems in computer science (which I can’t stand any more). But seriously, if you’re managing a cache like this, then cache invalidation really is tricky. When data in the underlying database changes, how do you know what entries in the cache to expire or update? One option is to have an expiry algorithm which figures out which database change affects which cache entries, but those algorithms are brittle and error-prone. Alternatively, you can just have a time-to-live (expiry time) and accept that you sometimes read stale data from the cache, but such staleness is often unacceptable.

The first problem is that clichéd quote about there being only two hard problems in computer science (which I can’t stand any more). But seriously, if you’re managing a cache like this, then cache invalidation really is tricky. When data in the underlying database changes, how do you know what entries in the cache to expire or update? One option is to have an expiry algorithm which figures out which database change affects which cache entries, but those algorithms are brittle and error-prone. Alternatively, you can just have a time-to-live (expiry time) and accept that you sometimes read stale data from the cache, but such staleness is often unacceptable.

Another problem is that this architecture is very prone to race conditions. For example, say you have two processes concurrently writing to the database and also updating the cache. They might update the database in one order, and the cache in the other order, and now the two are inconsistent. Or if you fill the cache on read, you may read and write concurrently, and so the cache is updated with a stale value while the concurrent write is occurring. I suspect that most of us building these systems just pretend that the race conditions don’t exist, because they are just too much to think about.

A third problem is cold start. If you reboot your memcached servers and they lose all their cached contents, suddenly every request is a cache miss, the database is overloaded because of the sudden surge in requests, and you’re in a world of pain. If you want to create a new cache, you need some way of bootstrapping its contents without overloading other parts of the system.

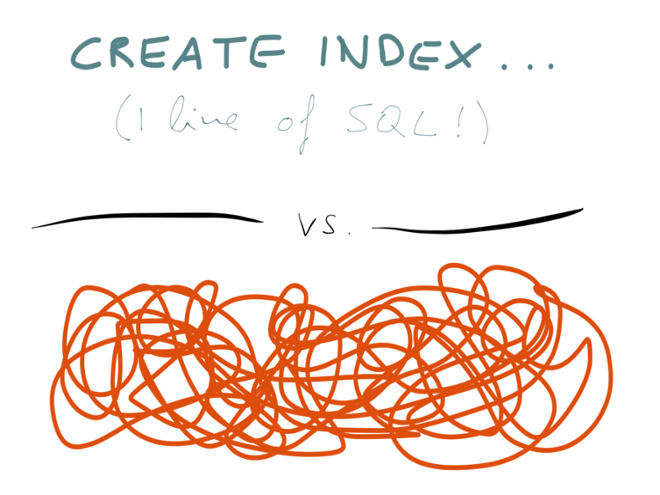

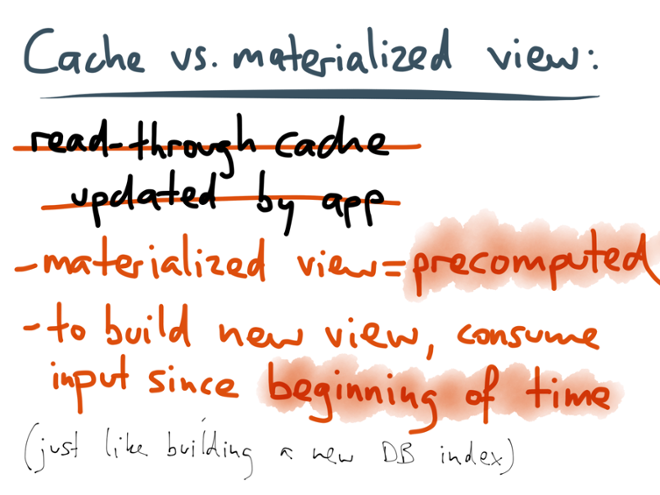

So, here we have a contrast: on the one hand, creating a secondary index in a database is beautifully simple, one line of SQL — the database handles it automatically, keeping everything up-to-date, and even making the index transactionally consistent. On the other hand, application-level cache maintenance is a complete mess of complicated invalidation logic, race conditions and operational problems.

Why should it be that way? Secondary indexes and caches are not fundamentally different. We said earlier that a secondary index is just a redundant data structure on the side, which structures the same data in a different way, in order to speed up read queries. A cache is just the same.

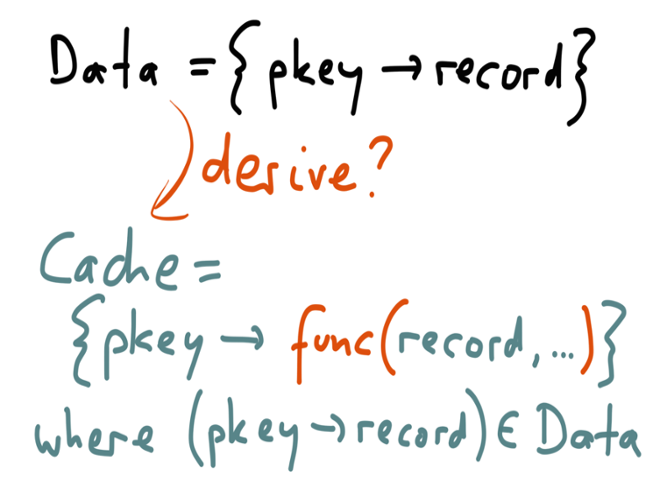

If you think about it, a cache is also the result of taking your data in one form (the form in which it’s stored in the database) and transforming it into a different form for faster reads. In other words, the contents of the cache are derived from the contents of the database.

We said that a secondary index is built by picking out one field from every record, and using that as the key in a dictionary. In the case of a cache, we may apply an arbitrary function to the data: the data from the database may have gone through some kind of business logic or rendering before it’s put in the cache, and it may be the result of joining several records from different tables. But the end result is similar: if you lose your cache, you can rebuild it from the underlying database; thus, the contents of the cache are derived from the database.

In a read-through cache, this transformation happens on the fly, when there is a cache miss. But we could perhaps imagine making the process of building and updating a cache more systematic, and more similar to secondary indexes. Let’s return to that idea later.

I said I was going to talk about four different aspects of database. Let’s move on to the fourth: materialized views.

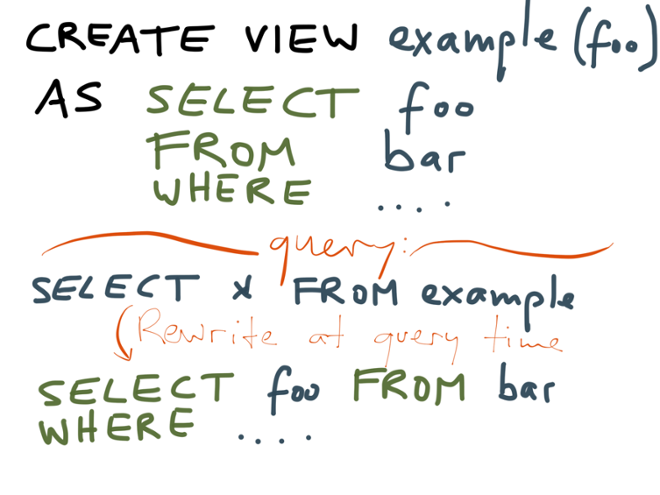

You may already know what materialized views are, but let me explain them briefly in case you’ve not previously come across them. You may be more familiar with “normal” views — non-materialized views, or virtual views, or whatever you want to call them. They work like this:

In a relational database, where views are common, you would create a view by saying “CREATE VIEW viewname…” followed by a SELECT query. When you now look at this view in the database, it looks somewhat like a table — you can use it in read queries like any other table. And when you do this, say you SELECT * from that view, the database’s query planner actually rewrites the query into the underlying query that you used in the definition of the view.

So you can think of a view as a kind of convenient alias, a wrapper that allows you to create an abstraction, hiding a complicated query behind a simpler interface.

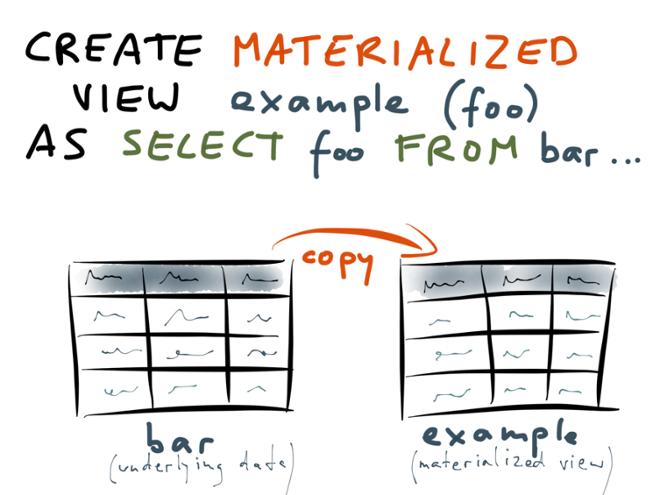

Contrast that with a materialized view, which is defined using almost identical syntax:

You also define a materialized view in terms of a SELECT query; the only syntactic difference is that you say CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW instead of CREATE VIEW. However, the implementation is totally different.

When you create a materialized view, the database starts with the underlying tables — that is, the tables you’re querying in the SELECT statement of the view (“bar” in the example). The database scans over the entire contents of those tables, executes that SELECT query on all of the data, and copies the results of that query into something like a temporary table.

The results of this query are actually written to disk, in a form that’s very similar to a normal table. And that’s really what “materialized” means in this context: it just means that the view’s query has been executed and the results written to disk.

Remember that with the non-materialized view, the database would expand the view into the underlying query at query time. On the other hand, when you query a materialized view, the database can read its contents directly from disk, just like a table. The view’s underlying query has already been executed ahead of time, so the database now just needs to read the result. This is especially useful if the view’s underlying query is expensive.

If you’re thinking “this seems like a cache of query results”, you would be right — that’s exactly what it is. However, the big difference between a materialized view and application-managed caches is the responsibility for keeping it up-to-date.

With a materialized view, you declare once how you want the materialized view to be defined, and the database takes care of building that view from a consistent snapshot of the underlying tables (much like building a secondary index). Moreover, when the data in the underlying tables changes, the database takes responsibility for maintaining the materialized view, keeping it up-to-date. Some databases do this materialized view maintenance on an ongoing basis, and some require you to periodically refresh the view so that changes take effect. But you certainly don’t have to do cache invalidation in your application code.

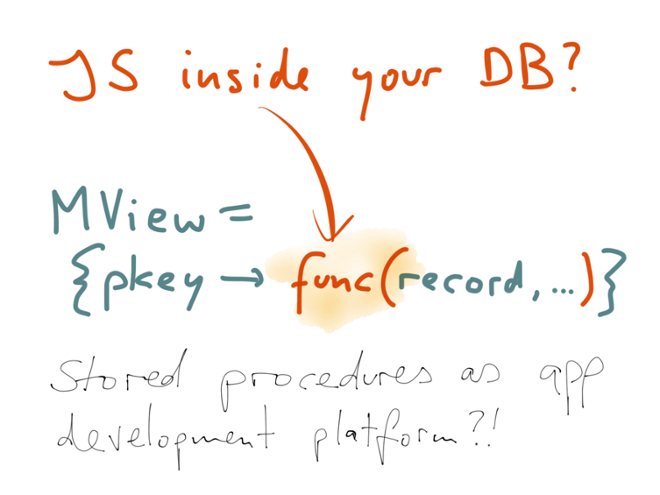

Another feature of application-managed caches is that you can apply arbitrary business logic to the data before storing it in the cache, so that you can do less work at query time, or reduce the amount of data you need to cache. Could a materialized view do something similar? In a relational database, materialized views are defined using SQL, so the transformations they can apply to the data are limited to the operations that are built into SQL (which are very restricted compared to a general-purpose programming language). However, many databases can also be extended using stored procedures — code that runs inside the database and can be called from SQL. For example, you can use JavaScript to write PostgreSQL stored procedures. This would let you implement something like an application-level cache, including arbitrary business logic, running as a materialized view inside a database.

In a relational database, materialized views are defined using SQL, so the transformations they can apply to the data are limited to the operations that are built into SQL (which are very restricted compared to a general-purpose programming language). However, many databases can also be extended using stored procedures — code that runs inside the database and can be called from SQL. For example, you can use JavaScript to write PostgreSQL stored procedures. This would let you implement something like an application-level cache, including arbitrary business logic, running as a materialized view inside a database.

I am not convinced that this is necessarily a good idea: with code running inside your database, it’s much harder to reason about monitoring, versioning, deployments, performance impact, multi-tenant resource isolation, and so on. I don’t think I would advocate stored procedures as an application development platform. However, the idea of materialized views is nevertheless interesting.

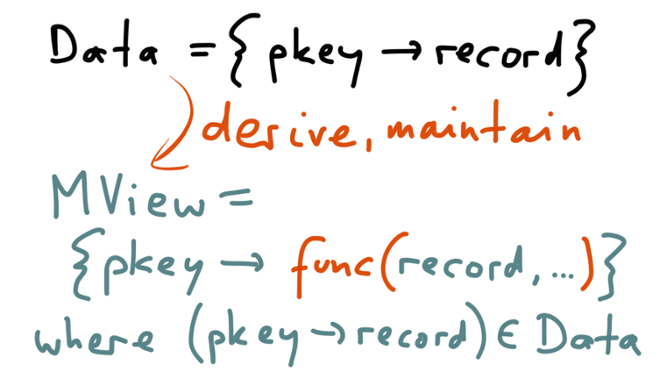

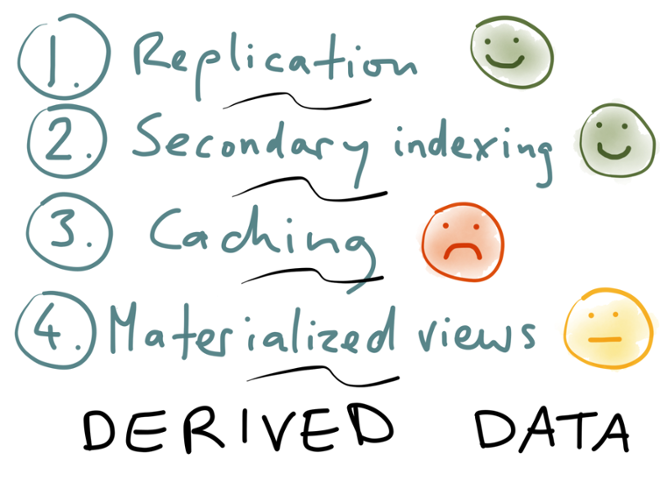

Let’s recap the four aspects of databases that we discussed: replication, secondary indexing, caching, and materialized views. What they all have in common is that they are dealing with derived data in some way: some secondary data structure is derived from an underlying, primary dataset, via a transformation process.

Let’s recap the four aspects of databases that we discussed: replication, secondary indexing, caching, and materialized views. What they all have in common is that they are dealing with derived data in some way: some secondary data structure is derived from an underlying, primary dataset, via a transformation process.

- We first discussed replication, i.e. keeping a copy of the same data on multiple machines. It generally works very well, so we’ll give it a green smiley. There are some operational quirks with some databases, and some of the tooling is a bit weird, but on the whole it’s mature, well-understood, and well-supported.

- Similarly, secondary indexing works very well. You can build a secondary index concurrently with processing write queries, and the database somehow manages to do this in a transactionally consistent way.

- On the other hand, application-level caching is a complete mess. Red frowny face.

- And materialized views are so-so: the idea is good, but the way they’re implemented is not what you’d want from a modern application development platform. Maintaining the materialized view puts additional load on the database, while actually the whole point of a cache is to reduce load on the database!

However, there’s something really compelling about this idea of materialized views. I see a materialized view almost as a kind of cache that magically keeps itself up-to-date. Instead of putting all of the complexity of cache invalidation in the application (risking race conditions and all the discussed problems), materialized views say that cache maintenance should be the responsibility of the data infrastructure.

However, there’s something really compelling about this idea of materialized views. I see a materialized view almost as a kind of cache that magically keeps itself up-to-date. Instead of putting all of the complexity of cache invalidation in the application (risking race conditions and all the discussed problems), materialized views say that cache maintenance should be the responsibility of the data infrastructure.

So let’s think about this: can we reinvent materialized views, implement them in a modern and scalable way, and use them as a general mechanism for cache maintenance?

So let’s think about this: can we reinvent materialized views, implement them in a modern and scalable way, and use them as a general mechanism for cache maintenance?

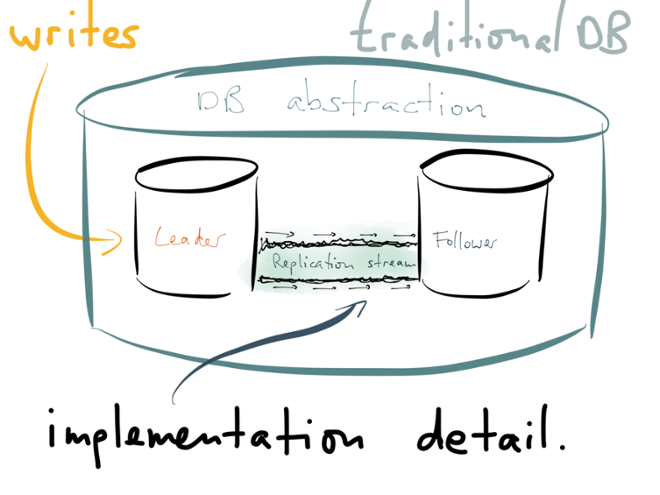

If we started with a clean slate, without the historical baggage of existing databases, what would the ideal architecture for applications look like? Think back to leader-based replication which we discussed earlier. You make your writes to a leader, which first applies the writes locally, and then sends those writes over the network to follower nodes. In other words, the leader sends a stream of data changes to the followers. We discussed a logical log as one way of implementing this.

Think back to leader-based replication which we discussed earlier. You make your writes to a leader, which first applies the writes locally, and then sends those writes over the network to follower nodes. In other words, the leader sends a stream of data changes to the followers. We discussed a logical log as one way of implementing this.

In a traditional database architecture, application developers are not supposed to think about that replication stream. It’s an implementation detail that is hidden by the database abstraction. SQL queries and responses are the database’s public interface — and the replication stream is not part of the public interface. You’re not supposed to go and parse that stream, and use it for your own purposes. (Yes, there are tools that do this, but in traditional databases they are on the periphery of what is supported, whereas the SQL interface is the dominant access method.)

And in some ways this is reasonable — the relational model is a pretty good abstraction, which is why it has been so popular for several decades. But SQL is not the last word in databases.

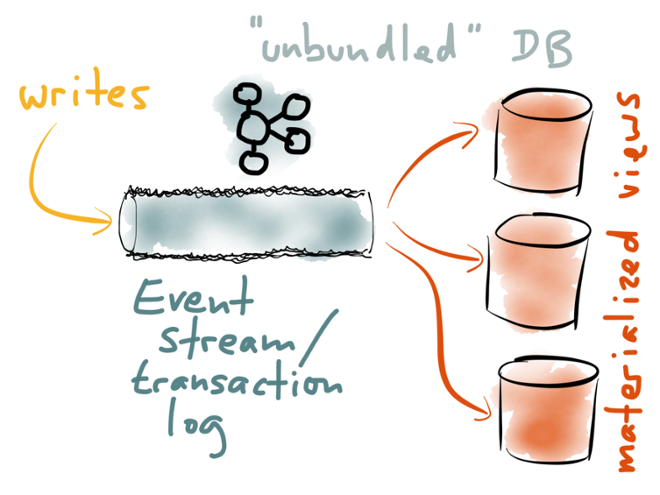

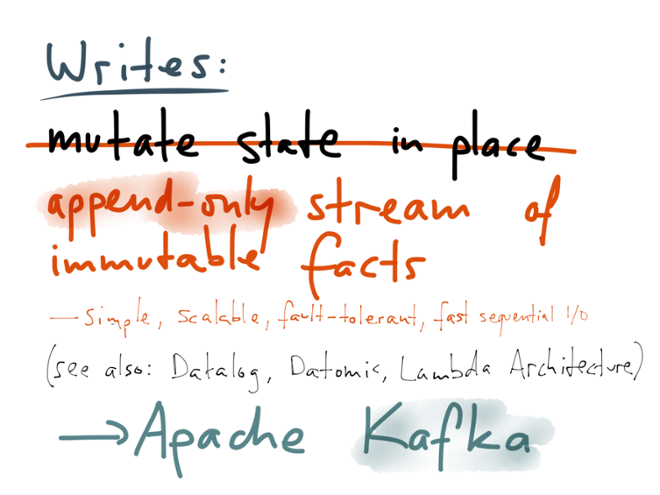

What if we took that replication stream, and made it a first-class citizen in our data architecture? What if we changed our infrastructure so that the replication stream was not an implementation detail, but a key part of the public interface of the database? What if we turn the database inside out, take the implementation detail that was previously hidden, and make it a top-level concern? What would that look like? Well, you could call that replication stream a “transaction log” or an “event stream”. You can format all your writes as immutable events (facts), like we saw earlier in the context of a logical log. Now each write is just an immutable event that you can append to the end of the transaction log. The transaction log is a really simple, append-only data structure.

Well, you could call that replication stream a “transaction log” or an “event stream”. You can format all your writes as immutable events (facts), like we saw earlier in the context of a logical log. Now each write is just an immutable event that you can append to the end of the transaction log. The transaction log is a really simple, append-only data structure.

There are various ways of implementing this, but one good choice for the transaction log is to use Apache Kafka. It provides an append-only log data structure, but it does so in a reliable and scalable manner — it durably writes everything to disk, it replicates data across multiple machines (so that you don’t lose any data if you lose a machine), and it partitions the stream across multiple machines for horizontal scalability. It easily handles millions of writes per second on very modest hardware.

When you do this, you don’t need to necessarily make your writes through a leader database — you could also imagine directly appending your writes to the log. (Going through a leader would still be useful if you want to validate that writes meet certain constraints before writing them to the log.)

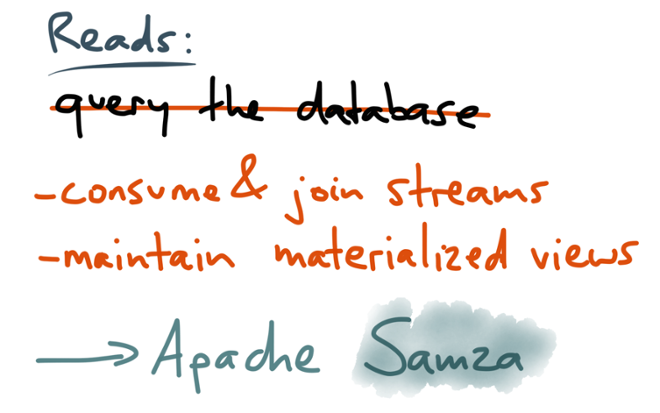

Writing to this system is now super fast and scalable, because the only thing you’re doing is appending an event to a log. But what about reads? Reading data that has been written to the log is now really inconvenient, because you have to scan the entire log to find the thing that you want.

The solution is to build materialized views from the writes in the transaction log. The materialized views are just like the secondary indexes we talked about earlier: data structures that are derived from the data in the log, and optimized for fast reading. A materialized view is just a cached subset of the log, and you could rebuild it from the log at any time. There could be many different materialized views onto the same data: a key-value store, a full-text search index, a graph index, an analytics system, and so on.

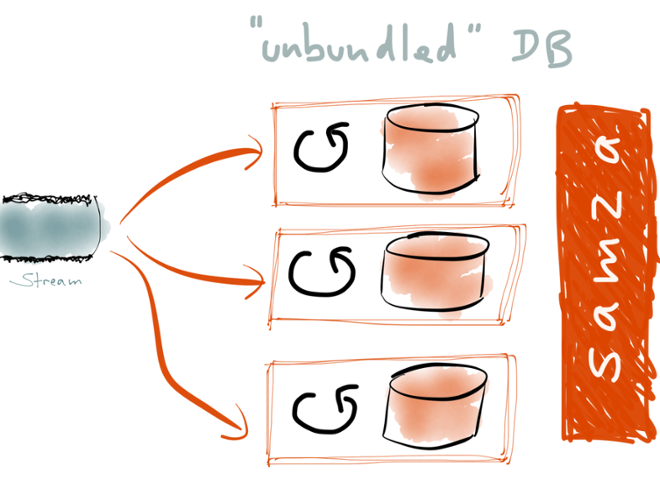

You can think of this as “unbundling” the database. All the stuff that was previously packed into a single monolithic software package is being broken out into modular components that can be composed in flexible ways. If you use Kafka to implement the log, how do you implement these materialized views? That’s where Apache Samza comes in. It’s a stream processing framework that is designed to go well with Kafka. With Samza, you write jobs that consume the events in a log, and build cached views of the data in the log. When a job first starts up, it can build up its state by consuming all the events in the log. And on an ongoing basis, whenever a new event appears in the stream, it can update the view accordingly. The view can be any existing database or index — Samza just provides the framework for processing the stream.

If you use Kafka to implement the log, how do you implement these materialized views? That’s where Apache Samza comes in. It’s a stream processing framework that is designed to go well with Kafka. With Samza, you write jobs that consume the events in a log, and build cached views of the data in the log. When a job first starts up, it can build up its state by consuming all the events in the log. And on an ongoing basis, whenever a new event appears in the stream, it can update the view accordingly. The view can be any existing database or index — Samza just provides the framework for processing the stream.

Anyone who wants to read data can now query those materialized views that are maintained by the Samza jobs. Those views are just databases, indexes or caches, and you can send read-only requests to them in the usual way. The difference to traditional database architecture is that if you want to write to the system, you don’t write directly to the same databases that you read from. Instead, you write to the log, and there is an explicit transformation process which takes the data on the log and applies it to the materialized views. This separation of reads and writes is really the key idea here. By putting writes only in the log, we can make them much simpler: we don’t need to update state in place, so we move away from the problems of concurrent mutation of global shared state. Instead, we just keep an append-only log of immutable events. This gives excellent performance (appending to a file is sequential I/O, which is much faster than random-access I/O), is easily scalable (independent events can be put in separate partitions), and is much easier to make reliable.

This separation of reads and writes is really the key idea here. By putting writes only in the log, we can make them much simpler: we don’t need to update state in place, so we move away from the problems of concurrent mutation of global shared state. Instead, we just keep an append-only log of immutable events. This gives excellent performance (appending to a file is sequential I/O, which is much faster than random-access I/O), is easily scalable (independent events can be put in separate partitions), and is much easier to make reliable.

If it’s too expensive for you to keep the entire history of every change that ever happened to your data, Kafka supports compaction, which is a kind of garbage collection process that runs in the background. It’s very similar to the log compaction that databases do internally. But that doesn’t change the basic principle of working with streams of immutable events.

These ideas are nothing new. To mention just a few examples, Event Sourcing is a data modelling technique based on the same principle; query languages like Datalog have been based on immutable facts for decades; databases like Datomic are built on immutability, enabling neat features like point-in-time historical queries; and the Lambda Architecture is one possible approach for dealing with immutable datasets at scale. At many levels of the stack, immutability is being applied successfully.

On the read side, we need to start thinking less about querying databases, and more about consuming and joining streams, and maintaining materialized views of the data in the form in which we want to read it.

To be clear, I think querying databases will continue to be important: for example, when an analyst is running exploratory ad-hoc queries against a data warehouse of historical data, it doesn’t make much sense to use materialized views — for those kinds of queries it’s better to just keep all the raw events, and to build databases which can scan over them very quickly. Modern column stores have become very good at that.

But in situations where you might use application-managed caches (namely, an OLTP context where the queries are known in advance and predictable), materialized views are very helpful. There are a few differences between a read-through cache (which gets invalidated or updated within the application code) and a materialized view (which is maintained by consuming a log):

There are a few differences between a read-through cache (which gets invalidated or updated within the application code) and a materialized view (which is maintained by consuming a log):

- With the materialized view, there is a principled translation process from the write-optimized data in the log into the read-optimized data in the view. That translation runs in a separate process which you can monitor, debug, scale and maintain independently from the rest of your application. By contrast, in the typical read-through caching approach, the cache management logic is deeply intertwined with the rest of the application, it’s easy to introduce bugs, and it’s difficult to understand what is happening.

- A cache is filled on demand when there is a cache miss (so the first request for a given object is always slow). By contrast, a materialized view is precomputed, i.e. its entire contents are computed before anyone asks for it — just like a secondary index. This means there is no such thing as a cache miss: if an item doesn’t exist in the materialized view, it doesn’t exist in the database. There is no need to fall back to some kind of underlying database.

- Once you have this process for translating logs into views, you have great flexibility to create new views: if you want to present your existing data in some new way, you can simply create a new stream processing job, consume the input log from the beginning, and thus build a completely new view onto all the existing data. (If you think about it, this is pretty much what a database does internally when you create a new secondary index on an existing table.) You can then maintain both views in parallel, gradually move applications to the new view, and eventually discard the old view. No more scary stop-the-world schema migrations.

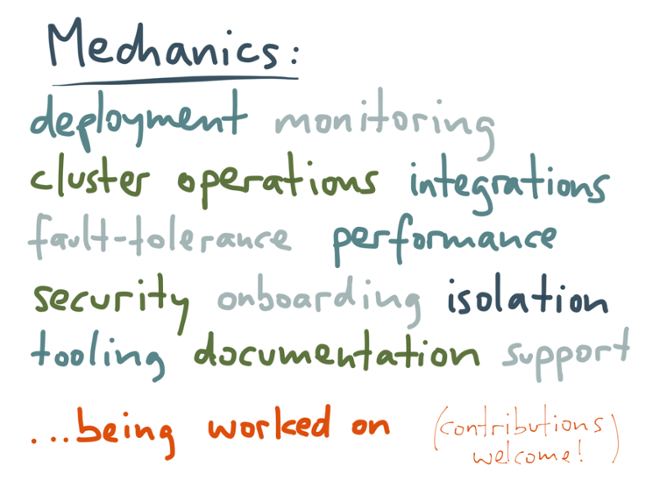

Of course, such a big change in application architecture and database architecture means that many practical details need to be figured out: how do you deploy and monitor these stream processing jobs, how do you make the system robust to various kinds of fault, how do you integrate with existing systems, and so on? But the good news is that all of these issues are being worked on. It’s a fast-moving area with lots of activity, so if you find it interesting, we’d love your contributions to the open source projects.

Of course, such a big change in application architecture and database architecture means that many practical details need to be figured out: how do you deploy and monitor these stream processing jobs, how do you make the system robust to various kinds of fault, how do you integrate with existing systems, and so on? But the good news is that all of these issues are being worked on. It’s a fast-moving area with lots of activity, so if you find it interesting, we’d love your contributions to the open source projects. We are still figuring out how to build large-scale applications well — what techniques we can use to make our systems scalable, reliable and maintainable. Put more bluntly, we need to figure out ways to stop our applications turning into big balls of mud.

We are still figuring out how to build large-scale applications well — what techniques we can use to make our systems scalable, reliable and maintainable. Put more bluntly, we need to figure out ways to stop our applications turning into big balls of mud.

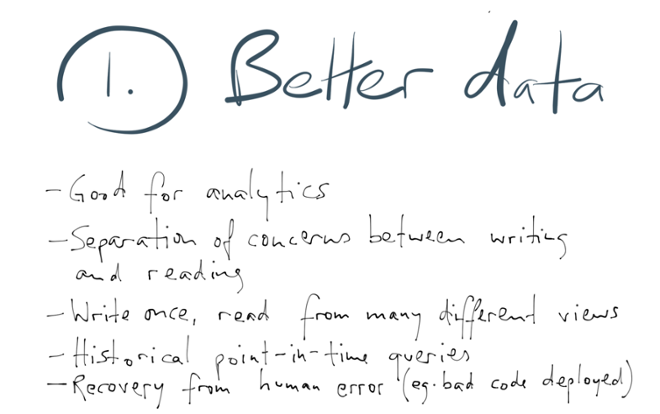

However, to me, this approach of immutable events and materialized views seems like a very promising route forwards. I am optimistic that this kind of application architecture will help us build better (more powerful and more reliable) software faster. The changes I’ve proposed are quite radical, and it’s going to be a lot of work to put them into practice. If we are going to completely change the way we use databases, we had better have some very good reasons. So let me give three reasons why I think it’s worth moving towards a log of immutable events.

The changes I’ve proposed are quite radical, and it’s going to be a lot of work to put them into practice. If we are going to completely change the way we use databases, we had better have some very good reasons. So let me give three reasons why I think it’s worth moving towards a log of immutable events.

Firstly, I think that writing data as a log produces better-quality data than if you update a database directly. For example, if someone adds an item to their shopping cart and then removes it again, those actions have information value. If you delete that information from the database when a customer removes an item from the cart, you’ve just thrown away information that would have been valuable for analytics and recommendation systems.

The entire long-standing debate about normalization in databases is predicated on the assumption that data is going to be written and read in the same schema. A normalized database (with no redundancy) is optimized for writing, whereas a denormalized database is optimized for reading. If you separate the writing side (the log) from the reading side (materialized views), you can denormalize the reading side to your heart’s content, but still retain the ability to process writes efficiently.

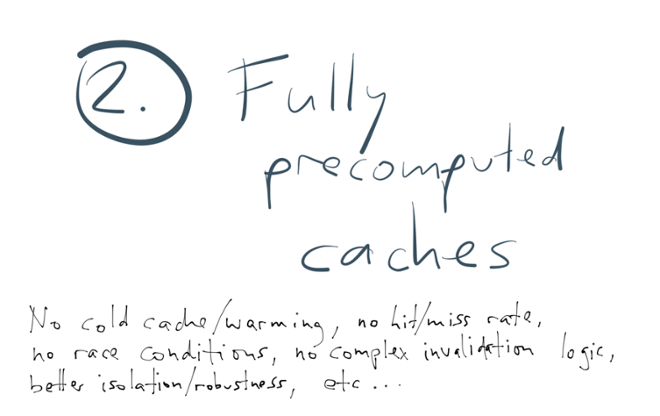

Another very nice feature of an append-only log is that it allows much easier recovery from errors. If you deploy some bad code that writes incorrect data to the database, or if a human enters some incorrect data, you can look at the log to see the exact history of what happened, and undo it. That kind of recovery is much harder if you’ve overwritten old data with new data, or even deleted data incorrectly. Also, any kind of audit is much easier if you only ever append to a log — that’s why accountants don’t use erasers. Secondly, we can fix all the problems of read-through caches that we discussed earlier. The cold start problem goes away, because we can simply precompute the entire contents of the cache (which also means there’s no such thing as a cache miss).

Secondly, we can fix all the problems of read-through caches that we discussed earlier. The cold start problem goes away, because we can simply precompute the entire contents of the cache (which also means there’s no such thing as a cache miss).

If materialized views are only ever updated via the log, then a whole class of race conditions goes away: the log defines the order in which writes are applied, so all the views that are based on the same log apply the changes in the same order, so they end up being consistent with each other. The log squeezes the non-determinism of concurrency out of the stream of writes.

What I particularly like is that this architecture helps enable agile, incremental software development. If you want to experiment with a new product feature, for which you need to present existing data in a new way, you can just build a new view onto your data without affecting any of the existing views. You can then show that view to a subset of users, and test whether it’s better than the old thing. If yes, you can gradually move users to the new view; if not, you can just drop the view as if nothing had happened. This is much more flexible than schema migrations, which are generally an all-or-nothing affair. Being able to experiment freely with new features, without onerous migration processes, is a tremendous enabler. My third reason for wanting to change database architecture is that it allows us to put streams everywhere. This point needs a bit more explanation.

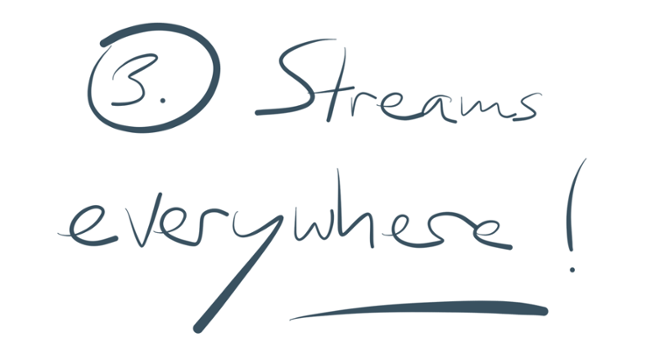

My third reason for wanting to change database architecture is that it allows us to put streams everywhere. This point needs a bit more explanation.

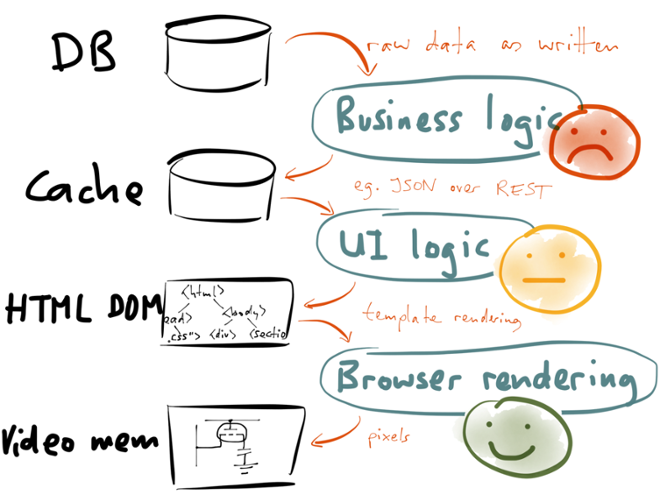

Imagine what happens when a user of your application views some data. In a traditional database architecture, the data is loaded from a database, perhaps transformed with some business logic, and perhaps written to a cache. Data in the cache is rendered into a user interface in some way — for example, by rendering it to HTML on the server, or by transferring it to the client as JSON and rendering it on the client.

The result of template rendering is some kind of structure describing the user interface layout: in a web browser, this would be the HTML DOM, and in a native application this would be using the operating system’s UI components. Either way, a rendering engine eventually turns this description of UI components into pixels in video memory, and this is what the user actually sees.

When you look at it like this, it looks very much like a data transformation pipeline. In fact, you can think of each lower layer as a materialized view of the upper layer: the cache is a materialized view of the database (the cache contents are derived from the database contents); the HTML DOM is a materialized view of the cache (the HTML is derived from the JSON stored in the cache); and the pixels in video memory are a materialized view of the HTML DOM (the rendering engine derives the pixels from the UI layout).

Now, how well does each of these transformation steps work? I would argue that web browser rendering engines are brilliant feats of engineering. You can use JavaScript to change some CSS class, or have some CSS rules conditional on mouse-over, and the rendering engine automatically figures out which rectangle of the page needs to be re-rendered as a result of the changes. It does hardware-accelerated animations and even 3D transformations. The pixels in video memory are automatically kept up-to-date with the underlying DOM state, and this very complex transformation process works remarkably well.

What about the transformation from data objects to user interface components? I’ve given it a yellow “so-so” smiley for now, as the techniques for updating user interface based on data changes are still quite new. However, they are rapidly maturing: on the web, frameworks like Facebook’s React, Angular and Ember are enabling user interfaces that can be updated from a stream, and Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) languages like Elm are in the same area. There is a lot of activity in this field, and it is rapidly maturing towards a green smiley.

However, the transformation from database writes to cache/materialized view updates is still mostly stuck in the dark ages. That’s what this entire talk is about: database-driven backend services are currently the weakest link in this entire data transformation pipeline. Even if the user interface can dynamically update when the underlying data changes, that’s not much use if the application can’t detect when data changes!

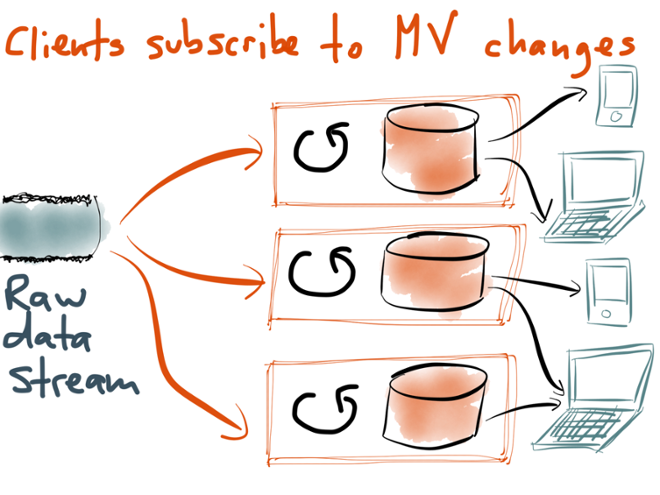

If we move to an architecture where materialized views are updated from a stream of changes, that opens up an exciting new prospect: when a client reads from one of these views, it can keep the connection open. If that view is later updated, due to some change that appeared in the stream, the server can use this connection to notify the client about the change (for example, using a WebSocket or Server-Sent Events). The client can then update its user interface accordingly.

If we move to an architecture where materialized views are updated from a stream of changes, that opens up an exciting new prospect: when a client reads from one of these views, it can keep the connection open. If that view is later updated, due to some change that appeared in the stream, the server can use this connection to notify the client about the change (for example, using a WebSocket or Server-Sent Events). The client can then update its user interface accordingly.

This means that the client is not just reading the view at one point in time, but actually subscribing to the stream of changes that may subsequently happen. Provided that the client’s internet connection remains active, the server can push any changes to the client. After all, why would you ever want outdated information on your screen if more recent information is available? The notion of static web pages, which are requested once and then never change, is looking increasingly anachronistic.

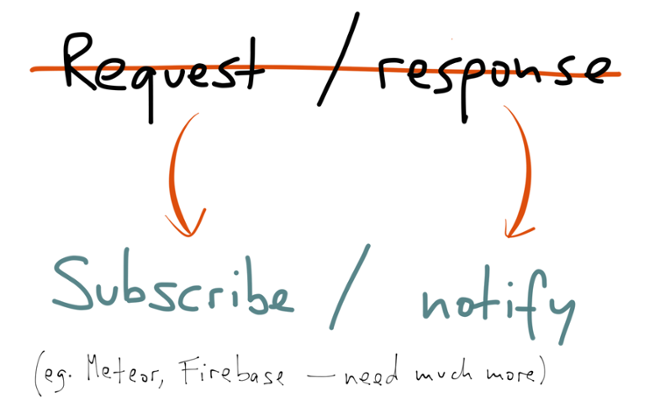

However, allowing clients to subscribe to changes in data requires a big rethink of the way we write applications. The request-response model is very deeply engrained in our thinking, in our network protocols and in our programming languages: whether it’s a request to a RESTful service, or a method call on an object, the assumption is generally that you’re going to make one request, and get one response. There’s generally no provision for an ongoing stream of responses. Basically, I’m saying that in the future, REST is not going to cut the mustard, because it’s based on a request-response model.

Instead of thinking of requests and responses, we need to start thinking of subscribing to streams and notifying subscribers of new events. And this needs to happen through all the layers of the stack — the databases, the client libraries, the application servers, the business logic, the frontends, and so on. If you want the user interface to dynamically update in response to data changes, that will only be possible if we systematically apply stream thinking everywhere, so that data changes can propagate through all the layers. I think we’re going to see a lot more people using stream-friendly programming models based on actors and channels, or reactive frameworks such as RxJava.

I’m glad to see that some people are already working on this. A few weeks ago RethinkDB announced that they are going to support clients subscribing to query results, and being notified if the query results change. Meteor and Firebase are also worth mentioning, as frameworks which integrate the database backend and user interface layers so as to be able to push changes into the user interface. These are excellent efforts. We need many more like them. This brings us to the end of this talk. We started by observing that traditional databases and caches are like global variables, a kind of shared mutable state that becomes messy at scale. We explored four aspects of databases — replication, secondary indexing, caching and materialized views — which naturally led us to the idea of streams of immutable events. We then looked at how things would get better if we oriented our database architecture around streams and materialized views, and found some compelling directions for the future.

This brings us to the end of this talk. We started by observing that traditional databases and caches are like global variables, a kind of shared mutable state that becomes messy at scale. We explored four aspects of databases — replication, secondary indexing, caching and materialized views — which naturally led us to the idea of streams of immutable events. We then looked at how things would get better if we oriented our database architecture around streams and materialized views, and found some compelling directions for the future.

Fortunately, this is not science fiction — it’s happening now. People are working on various parts of the problem and finding good solutions. The tools at our disposal are rapidly becoming better. It’s an exciting time to be building software.

If this excessively long article was not enough, and you want to read even more on the topic, I would recommend:

- My upcoming book, Designing Data-Intensive Applications, systematically explores the architecture of data systems. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy the book too.

- I previously wrote about similar ideas in 2012, from a different perspective, in a blog post called “Rethinking caching in web apps.”

- Jay Kreps has written several highly relevant articles, in particular about logs as a fundamental data abstraction, about the lambda architecture, and about stateful stream processing.

- The most common question people ask is: “but what about transactions?” — This is a somewhat open research problem, but I think a promising way forward would be to layer a transaction protocol on top of the asynchronous log. Tango (from Microsoft Research) describes one way of doing that, and Peter Bailis et al.’s work on highly available transactions is also relevant.

- Pat Helland has been preaching this gospel for ages. His latest CIDR paper Immutability Changes Everything is a good summary.

- There is a a more applied guide to putting stream data to work in a company here.

- Those in the Bay Area who are interested in learning more about Apache Samza should consider attending the Samza meet-up tonight.

Did you like this blog post? Share it now

Subscribe to the Confluent blog

Building Streaming Data Pipelines, Part 1: Data Exploration With Tableflow

This blog post demonstrates using Tableflow to easily transform Kafka topics into queryable Iceberg tables. It uses UK Environment Agency sensor data as a data source, and shows how to use Tableflow with standard SQL to explore and understand the data.

Guide to Consumer Offsets: Manual Control, Challenges, and the Innovations of KIP-1094

The guide covers Kafka consumer offsets, the challenges with manual control, and the improvements introduced by KIP-1094. Key enhancements include tracking the next offset and leader epoch accurately. This ensures consistent data processing, better reliability, and performance.